2007 was a year of trends aplenty, both overwrought and unspoken. Amidst the landfall of gargantuan threequels (of which few were worth their weight in box office figures) were a plethora of savory revisionist westerns (

The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford,

There Will Be Blood,

No Country For Old Men), documentaries about topics both great (

Operation Homecoming,

Into Great Silence) and small (

Helvetica,

Rolling Like a Stone,

The King of Kong: A Fistful of Quarters,

The Cats of Mirikatani), and an unofficial trilogy of mind-blowing action films (

Exiled,

War,

Shoot ‘Em Up) that, through their own particular stylistic indulgences, looked at masculine codes of honor in ways both thrilling and humorous. Iraq dominated the multiplex in theory only, with the limp diatribes of

In the Valley of Elah and

Rendition disappearing almost without a trace, while two of the year’s finest releases were actually revamped staples from cinema past: Charles Burnett’s 1977 masterpiece

Killer of Sheep, and the latest (final?) version of Ridley Scott’s almost-as-great

Blade Runner. It was a prolific year for animation, from the no-holds-barred surrealist firebomb that was

Aqua Teen Hunger Force Colon Movie Film For Theaters to the timeless American familial values of

The Simpsons Movie to the dreamy landscapes of

Paprika to

Ratatouille’s effortless splendor to the political upheaval of

Persepolis. McLovin’ and Spider-Pig rightfully seized the box office, while it was the year’s onslaught of gritty, no-frills genre pictures (

Eastern Promises,

We Own the Night,

Black Snake Moan) that proved the necessary antidote to the rancid Zack Snyder/Frank Miller collaboration

300. A pair of nifty Stephen King adaptations (

1408,

The Mist) and two of the greatest zombie-ish films ever made (

28 Weeks Later,

Planet Terror) assured us that horror isn't dead, despite the hollow flogging emphasized by so many of the genre. The year’s worst films shared amongst them a single defining trait: more so than technical or artistic failings, they were one and all exercises in turgid and unjustified nihilism, marketing misanthropy as the new cool whilst further desensitizing their audiences to the far-reaching pains of the world.

French fries. A milkshake. A meatball. Masterpieces come in all shapes and sizes, and the feature-length adaptation of Cartoon Network's ultra-surrealist

Aqua Teen Hunger Force is an act of cinematic anarchy for the ages, dispensing of audience pretensions in a matter of moments before free-falling into a flabbergasting anti-narrative that exists somewhere between dadaist upheaval and Warholian self-examination.

The Simpsons has always been more loving and

South Park more scathing in their respective satires, but none is so subversively and forcefully deconstructive as this insane pop culture jambalaya.

The title of Paul Thomas Anderson's fifth feature is a promise to be fulfilled, for sure, but most intense about this epic adaptation of Upton Sinclair's

Oil! is his utter refusal to sympathize with Daniel Day-Lewis' brutal Daniel Plainview. Alternately (sometimes simultaneously) horrifying and bemusing,

There Will Be Blood rumbles like a turgid well before its histrionic breaking point, a regressive exclamation point that calls to attention our own self-destructive obsessions with money and faith.

A sermon-like immersion on an unprecedented scale,

Into Great Silence is the

2001: A Space Odyssey of documentaries, touching the infinite in its somber, restrained examination of religious life. Patience and meditation give way to enlightenment and transcendence, and so too does Philip Gröning's film reward our inquisition with invaluable wisdom on how best to live our lives.

Death is coming for us all, and all we can hope to do is to live with love and virtue before he comes knocking on our door. The Coens' meditation on fate and chance strikes chords at once universal and specific to our own time, while their cagey aesthetics - like Chigurh's restrained menace - continuously suggest a beast about to break free from its cage. Our suspense is baited not just for the lives of the characters on screen, but our own.

Zodiac is so blatantly anti-film in its construction that it could have been a documentary. David Fincher opts for the subtle underpass to his trademark stylistic flourishes and the result may be his best film to date, an absorbing look into the nature of obsession: for life, for power, for meaning, for truth. The intangible nature of each represents

Zodiac's devastating "based on a true story" relevance.

Following

Spider and

A History of Violence,

Eastern Promises continues David Cronenberg's shift from physical explorations to those more intangible. A mother without her daughter and a daughter without her mother represent the film's unspoken moral axis, while it is Cronenberg's delineating camera that most effectively gets to the bottom of his character's dichotomous identities.

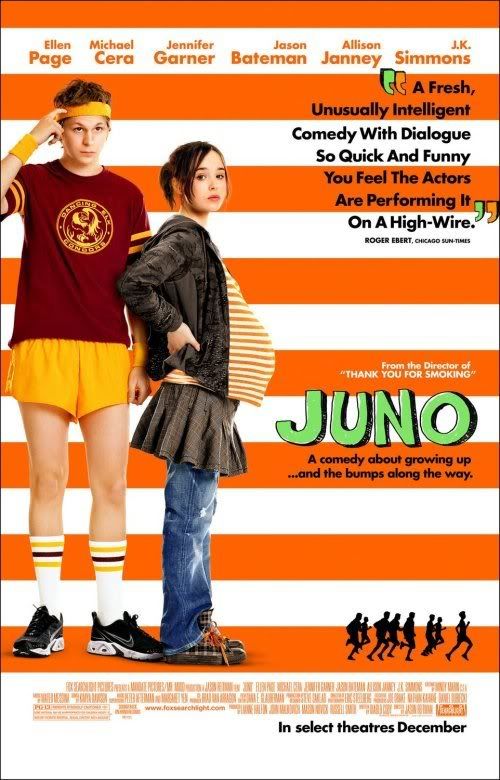

Anderson will always be trounced upon by those who mindlessly equate quirk with superficiality, lest they actually deal with things on a case by case basis. Unlike the cute but simplistic

Juno, Anderson uses his touches not as substance but as flourishes, moments and memories infused into compact packages that speak for more than the sum of their parts.

Hotel Chevalier may be his finest hour yet, squeezing enough pain and longing into less than a quarter of an hour so as to rival his own feature-length masterpieces.

Films are our dreams and wishes, and

Paprika's self-devouring chaos proves an inescapable journey down the rabbit hole of our collective yearning for meaning and truth. Satoshi Kon's latest animated masterwork escapes contrivance by allowing its characters to stand defined through their actions, explaining its heady sci-fi narrative only just enough to send us on our own way into the abyss.

No unnecessary sequel of the past ten years has been as profoundly realized as Juan Carlos Fresnadillo's survival extravaganza, exploding out of an otherworldly ether as it propels the general storyline of Danny Boyle's original film into areas more fable-esque than straight horror. The ties of blood are strongly felt as the sins of our fathers return to haunt us - often in ways unseen, but here as violent and bloody as ever.

Herzog's films have never existed in a context larger than that which they fashion for themselves, and it is in this way that

Rescue Dawn's Dieter Dengler ascends to the same heights of primordial experience as Aguirre or Fitzcarraldo. At war with both man and nature, his transformation reflects not only the duties and necessities of the soldier in combat, but the malleability and endurance of the human spirit.

12:08 East of Bucharest,

Ratatouille,

Death Proof,

Rolling Like a Stone,

Exiled,

Broken English,

Superbad,

Black Snake Moan,

The Taste of Tea,

Helvetica

Hostel: Part II,

I Know Who Killed Me,

Zzyzx,

Bratz,

Park,

Captivity,

Smokin' Aces,

300,

Behind the Mask: The Rise of Leslie Vernon,

Shrek the Third