Harry Potter films - such as they must exist, given their tentpole status for Warner Brothers - seem to require certain concessions from everyone outside the core target of Fans of the Books. Rather than attempting immersion on purely cinematic levels, a consideration of these films seems fair only when hinged on such "under the circumstances" attributes; only the bold Alfonso Cuaron totally broke free from studio oversight (or at least felt like he did) in Prisoner of Azkaban, the third film. Now three films worth of aesthetic recoil later, The Half-Blood Prince comes to us encumbered by similar issues of narrative balance as the majority of its predecessors - what matters to making this a good film versus what matters in selling this to a zealot-like audience? Personally, I prefer coming to these films as I always have - fan of the books, but with only faint memories of reading them (I've only read the first more than once). Tellingly, the best of the films have been those that made me feel least like I was re-reading their source material on the screen, and so I found Prince's almost whispy, broad-stroke handling of the plot more satisfying in the manner of pure cinema than that of a tedious connecting of the dots. Not every decision made in streamlining this story was wise, however - the climax is foreshadowed for virtually the entire film, first breathtakingly subtle (in an opening pre-title scene with Harry and Dumbledore) , but only to go directly into thuddening blatancy. Visual and verbal wit reigns as the special of the day, however (yes, this is how some high schoolers talk), while thoughtful compositions, in their vast, almost embracing depth, suggest a silent film made today. The effects are less annoyingly attention-grabbing than I'd come to anticipate - instead, they're more texturally banal so as to ground the proceedings in a believable habitat in which magic is a simple fact of life (as opposed to a box office draw). Were the film more consistently awe-inspiring (a madhouse chase through a wheat field suggests the Days of Heaven climax by way of Lynch), or the cast but a sliver more emotionally game (while quite honed and precise in their ever-deepening displays, these veterans nevertheless seem a little tired, even if such is otherwise appropriate given the long-term status of their characters' plights), and this might have been the most sterling Potter entry to date. Such as it is at first glance, it comes close.

Harry Potter films - such as they must exist, given their tentpole status for Warner Brothers - seem to require certain concessions from everyone outside the core target of Fans of the Books. Rather than attempting immersion on purely cinematic levels, a consideration of these films seems fair only when hinged on such "under the circumstances" attributes; only the bold Alfonso Cuaron totally broke free from studio oversight (or at least felt like he did) in Prisoner of Azkaban, the third film. Now three films worth of aesthetic recoil later, The Half-Blood Prince comes to us encumbered by similar issues of narrative balance as the majority of its predecessors - what matters to making this a good film versus what matters in selling this to a zealot-like audience? Personally, I prefer coming to these films as I always have - fan of the books, but with only faint memories of reading them (I've only read the first more than once). Tellingly, the best of the films have been those that made me feel least like I was re-reading their source material on the screen, and so I found Prince's almost whispy, broad-stroke handling of the plot more satisfying in the manner of pure cinema than that of a tedious connecting of the dots. Not every decision made in streamlining this story was wise, however - the climax is foreshadowed for virtually the entire film, first breathtakingly subtle (in an opening pre-title scene with Harry and Dumbledore) , but only to go directly into thuddening blatancy. Visual and verbal wit reigns as the special of the day, however (yes, this is how some high schoolers talk), while thoughtful compositions, in their vast, almost embracing depth, suggest a silent film made today. The effects are less annoyingly attention-grabbing than I'd come to anticipate - instead, they're more texturally banal so as to ground the proceedings in a believable habitat in which magic is a simple fact of life (as opposed to a box office draw). Were the film more consistently awe-inspiring (a madhouse chase through a wheat field suggests the Days of Heaven climax by way of Lynch), or the cast but a sliver more emotionally game (while quite honed and precise in their ever-deepening displays, these veterans nevertheless seem a little tired, even if such is otherwise appropriate given the long-term status of their characters' plights), and this might have been the most sterling Potter entry to date. Such as it is at first glance, it comes close.

Jul 15, 2009

Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince (2009): B

Harry Potter films - such as they must exist, given their tentpole status for Warner Brothers - seem to require certain concessions from everyone outside the core target of Fans of the Books. Rather than attempting immersion on purely cinematic levels, a consideration of these films seems fair only when hinged on such "under the circumstances" attributes; only the bold Alfonso Cuaron totally broke free from studio oversight (or at least felt like he did) in Prisoner of Azkaban, the third film. Now three films worth of aesthetic recoil later, The Half-Blood Prince comes to us encumbered by similar issues of narrative balance as the majority of its predecessors - what matters to making this a good film versus what matters in selling this to a zealot-like audience? Personally, I prefer coming to these films as I always have - fan of the books, but with only faint memories of reading them (I've only read the first more than once). Tellingly, the best of the films have been those that made me feel least like I was re-reading their source material on the screen, and so I found Prince's almost whispy, broad-stroke handling of the plot more satisfying in the manner of pure cinema than that of a tedious connecting of the dots. Not every decision made in streamlining this story was wise, however - the climax is foreshadowed for virtually the entire film, first breathtakingly subtle (in an opening pre-title scene with Harry and Dumbledore) , but only to go directly into thuddening blatancy. Visual and verbal wit reigns as the special of the day, however (yes, this is how some high schoolers talk), while thoughtful compositions, in their vast, almost embracing depth, suggest a silent film made today. The effects are less annoyingly attention-grabbing than I'd come to anticipate - instead, they're more texturally banal so as to ground the proceedings in a believable habitat in which magic is a simple fact of life (as opposed to a box office draw). Were the film more consistently awe-inspiring (a madhouse chase through a wheat field suggests the Days of Heaven climax by way of Lynch), or the cast but a sliver more emotionally game (while quite honed and precise in their ever-deepening displays, these veterans nevertheless seem a little tired, even if such is otherwise appropriate given the long-term status of their characters' plights), and this might have been the most sterling Potter entry to date. Such as it is at first glance, it comes close.

Harry Potter films - such as they must exist, given their tentpole status for Warner Brothers - seem to require certain concessions from everyone outside the core target of Fans of the Books. Rather than attempting immersion on purely cinematic levels, a consideration of these films seems fair only when hinged on such "under the circumstances" attributes; only the bold Alfonso Cuaron totally broke free from studio oversight (or at least felt like he did) in Prisoner of Azkaban, the third film. Now three films worth of aesthetic recoil later, The Half-Blood Prince comes to us encumbered by similar issues of narrative balance as the majority of its predecessors - what matters to making this a good film versus what matters in selling this to a zealot-like audience? Personally, I prefer coming to these films as I always have - fan of the books, but with only faint memories of reading them (I've only read the first more than once). Tellingly, the best of the films have been those that made me feel least like I was re-reading their source material on the screen, and so I found Prince's almost whispy, broad-stroke handling of the plot more satisfying in the manner of pure cinema than that of a tedious connecting of the dots. Not every decision made in streamlining this story was wise, however - the climax is foreshadowed for virtually the entire film, first breathtakingly subtle (in an opening pre-title scene with Harry and Dumbledore) , but only to go directly into thuddening blatancy. Visual and verbal wit reigns as the special of the day, however (yes, this is how some high schoolers talk), while thoughtful compositions, in their vast, almost embracing depth, suggest a silent film made today. The effects are less annoyingly attention-grabbing than I'd come to anticipate - instead, they're more texturally banal so as to ground the proceedings in a believable habitat in which magic is a simple fact of life (as opposed to a box office draw). Were the film more consistently awe-inspiring (a madhouse chase through a wheat field suggests the Days of Heaven climax by way of Lynch), or the cast but a sliver more emotionally game (while quite honed and precise in their ever-deepening displays, these veterans nevertheless seem a little tired, even if such is otherwise appropriate given the long-term status of their characters' plights), and this might have been the most sterling Potter entry to date. Such as it is at first glance, it comes close.

Jul 3, 2009

Public Enemies (2009): A-

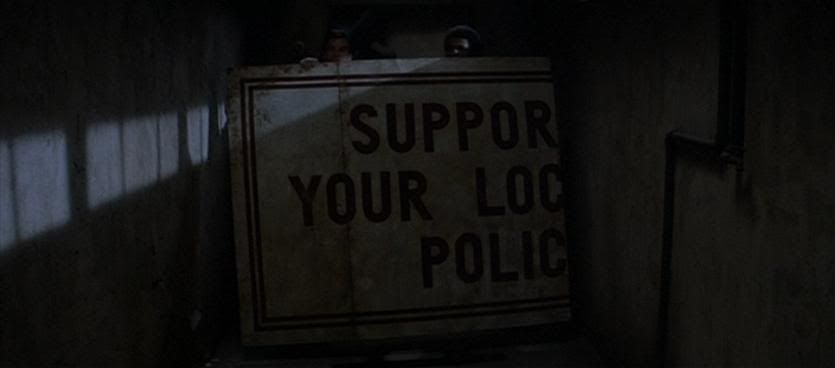

If Miami Vice was Michael Mann's freestyle celebration of identity and the need for spiritual release, Public Enemies is that work's paralleling, appropriately somber meditation on mortality - a harrowing rattle from its opening scenes of shackled prisoners marching in unison through the subsequent, episodic exploits in which legendary gangster John Dillinger and his cohorts fall to the determined lawmen in pursuit. Comparable to Heat's cop/criminal plot structure in surface details only, Enemies' primary characters aren't defined so much by existential hang-ups as they are by hunger for life. "I want it all, right now" tells Dillinger (Johnny Depp) after wooing lower class beauty Billie Frechette (Marion Cottilard); Christian Bale, effectively correcting his egotistical turn in Terminator Salvation, siphers off any trace of movie star charisma with exquisite understatedness as FBI agent Melvin Purvis, head of the team assigned to capture Dillinger. Though less ravishing than Vice, Public Enemies again finds Mann forging new ground in the digital arts; heavy grain emphasizes an anti-romantic view of material typically overshadowed by its own cinematic mythology, a subversive choice that comes full circle when Dillinger attends a Clarke Gable gangster film on the night of his death. Public Enemies diminishes one's expected visceral distance - every gunshot and bloodstain bears the heft of an unfolding present tense, none more cage-rattling than the chilling image of Baby Face Nelson (Stephen Graham) firing erratically as bullets riddle his chest, collapsing only to exhale a final, frosty breath.

If Miami Vice was Michael Mann's freestyle celebration of identity and the need for spiritual release, Public Enemies is that work's paralleling, appropriately somber meditation on mortality - a harrowing rattle from its opening scenes of shackled prisoners marching in unison through the subsequent, episodic exploits in which legendary gangster John Dillinger and his cohorts fall to the determined lawmen in pursuit. Comparable to Heat's cop/criminal plot structure in surface details only, Enemies' primary characters aren't defined so much by existential hang-ups as they are by hunger for life. "I want it all, right now" tells Dillinger (Johnny Depp) after wooing lower class beauty Billie Frechette (Marion Cottilard); Christian Bale, effectively correcting his egotistical turn in Terminator Salvation, siphers off any trace of movie star charisma with exquisite understatedness as FBI agent Melvin Purvis, head of the team assigned to capture Dillinger. Though less ravishing than Vice, Public Enemies again finds Mann forging new ground in the digital arts; heavy grain emphasizes an anti-romantic view of material typically overshadowed by its own cinematic mythology, a subversive choice that comes full circle when Dillinger attends a Clarke Gable gangster film on the night of his death. Public Enemies diminishes one's expected visceral distance - every gunshot and bloodstain bears the heft of an unfolding present tense, none more cage-rattling than the chilling image of Baby Face Nelson (Stephen Graham) firing erratically as bullets riddle his chest, collapsing only to exhale a final, frosty breath.

Jul 2, 2009

The On-Line Review Presents: The 50 Greatest Films

Iain Stott of The On-Line Review is asking critics and film-lovers to compile lists of their choices for the "fifty greatest films". For my own purposes, I made this as much of a balance as possible between personal favorites and - as near as anyone can objectively tell such a thing - the actual "best" films I've seen. Many that I weren't able to include damn near broke my heart; apologies, in no particular order, to James Cameron, Charlie Chaplin, Sergio Leone, Luis Buñuel, Dario Argento, Michael Mann, Milos Forman, Paul Thomas Anderson, Wes Anderson, Jonathan Demme, F.W. Murnau, Quentin Tarantino, Abbas Kiarostami, James Whale, Harold Ramis, Sophia Coppola, Hiroshi Shimizu, Peter Jackson, and many more. I'd rather not have anyone think of this as a definitive selection, but rather an in-the-moment representation of the works that I consider most important and influential to myself (even then, I'd probably have had to include another 50 just to cover all the essentials). Below is my photo essay top ten.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)