Five years later and Ang Lee’s audacious addition to the superhero genre remains among the most misunderstood creations of its time, as hindered by audience expectations (who seem to watch films more for specific components than any sense of search or want for discovery, especially amongst the intended audiences of this genre) as by its own multilayered complexities and occasionally overreaching hindrances. Just as often as with people, we like some movies for their strengths while finding that we love others for their flaws. Half a decade hasn’t yet diminished Hulk’s numerous potholes but the retrospect has further illuminated its groundbreaking efforts, strengthening those whose creativity and stamina are rooted equally in the reflexivity of cinema and the implied visual dynamics of the comic book panel.

As far as genre infusions go, Hulk defies categorization, both in terms of its illustrated source material and its stylistic executions. I’ll say right up front: I’ve never read a page of any comic featuring “The Incredible Hulk” and I don’t see myself getting around to it in the near future (so the rules say, never see a movie with an expert on its subject matter). Cinema, at its purest, glides through drama, while adherence to external rules (be they the concrete rules of our physical world or the pre-existing culture surrounding a chosen topic, hence disapproving fanboys deprived of Hulk Smash! adrenaline) are less important to any particular work than is its ability to function according to its own established modes of logic. Faithfulness never guarantees a good adaptation (yet another assumption extending from cinema’s misinterpreted literary functions), and whether it’s Spider-Man or Pride & Prejudice, every adaptation has the inalienable right – to be frank – to do whatever the hell it wants.

As far as genre infusions go, Hulk defies categorization, both in terms of its illustrated source material and its stylistic executions. I’ll say right up front: I’ve never read a page of any comic featuring “The Incredible Hulk” and I don’t see myself getting around to it in the near future (so the rules say, never see a movie with an expert on its subject matter). Cinema, at its purest, glides through drama, while adherence to external rules (be they the concrete rules of our physical world or the pre-existing culture surrounding a chosen topic, hence disapproving fanboys deprived of Hulk Smash! adrenaline) are less important to any particular work than is its ability to function according to its own established modes of logic. Faithfulness never guarantees a good adaptation (yet another assumption extending from cinema’s misinterpreted literary functions), and whether it’s Spider-Man or Pride & Prejudice, every adaptation has the inalienable right – to be frank – to do whatever the hell it wants.

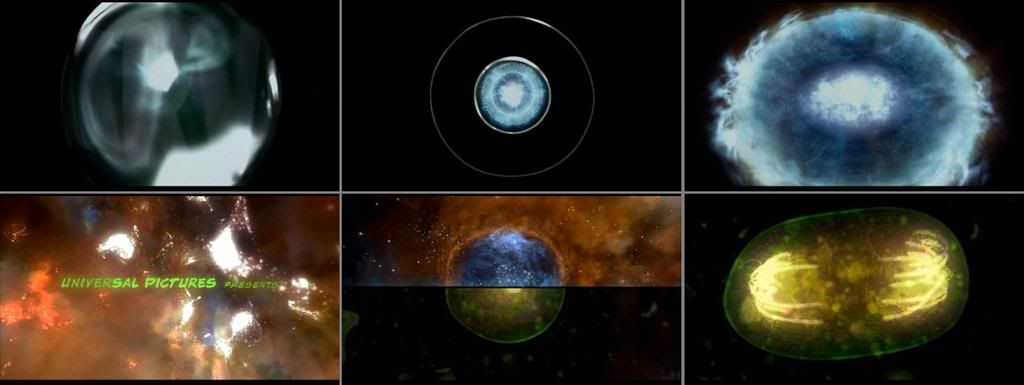

The opening credits of Hulk are a movie unto themselves, the green-tinged Marvel logo disappearing into a drop of water that triggers the films own Big Bang – an exploding universe of galaxies, nebulas, and synapses from which the first cells of life develop, mutate and divide, quickly growing beyond nature and into the burden of consciousness. Lee’s montage here is infectious, tracking the origins of the Hulk amid test tubes, experiments and lab notes with enough efficiency as to effectively summarize an entire prequel. As complimented by Danny Elfman’s equally underrated score – a perpetually downward spiral of psycho-spiritual chaos – it’s the overture to all that follows, declaring itself grandiose and impressionistic, favoring emotionally abstract imagery over realistic representations (although, as a former student of genetics, the basic groundwork is, at the least, fairly accurate). In its best moments, it brings to mind none other than Buñuel’s Un Chien Andalou (available here; watch it, because if you haven’t seen Un Chien Andalou, you haven’t seen jack).

A momentary diversion for clarification purposes. Above you will see a screen cap of the films title, spiraling out of and back into a genetic code. What do you see? More specifically, what don’t you see? “The”. For the last god damn freaking time, the title is Hulk (to date, only Roger Ebert has written about the film more than once and continued to address it correctly). This has as much to do with how we consume our movies as it does my own anal pet peeves (I’m similarly staunch about the non-“The” School of Rock). Not once in Ang Lee’s film is the word “incredible” used, and “hulk” only makes a singular, practically incidental appearance. As represented by the title, Hulk isn’t a physical thing – it’s a mentality, an idea, manifest of the materials implicit evolutionary connotations (an equally appropriate title had already been used, that being Ken Russell’s Altered States). Try getting that across to audiences expecting familiarity (thus pandering) and you’ll know the experience of pounding one’s head into a brick wall.

As Hulk continues, Lee’s nerve astonishes even as his moments of inarticulate conception stick out like sore thumbs. Much has been made of the films comic book visual design, though these acknowledgements, be they positive or negative, have done more damage understanding of the film than anything in that they’re almost exclusively limited to the films more literal screen divisions, in which separate panels appear and disappear, pan and fade in an effort to recreate a traditionally printed artifice. More important are the films no less explicit but infinitely more balanced fades, cuts, and blends, traditional cinematic devices given new potency via almost perfectly conceived stylistic utilizations, channeling the inherently static dynamics of graphic novel language into a distinctly filmic form.

More than anything, Hulk is about images clashing together, and Lee’s best decisions are not unlike the overlapping pieces of an orchestra. Amongst almost countless examples are the contours of scribbled lab notes morphing into the eye of a reptile (see above), whereas the headlights of a car blur into the form of the full moon. Climaxing in a multi-panel sequence (reminiscent of Harryhausen stop-motion techniques) in which the Hulk (Eric Bana, when not in mandatory CGI form) and an energy-transformed David Banner (Nick Nolte, ditto electrifying special effects) battle amongst the nighttime sky, leaping from cloud to cloud via bolts of lightning, such are the highlights of Hulk’s dynamic vocabulary of images, though not without a few sore spots. The majority of such are among the misguided split-screen compositions, which too often clutter the frame with varying angles and viewpoints that reveal no more information together than apart (no choice is more disastrous, though, than Josh Lucas’ hilarious death). Credit, though, to those that effectively emulate cinematic shot/reverse shot techniques within multi-layered panel frames (see the Hulk’s escape from the government lab), imperfectly yet poetically signifying Hulk’s own distinct qualities while collapsing otherwise routine exposition into something more flavorful.

Freud gets tossed around a lot when Hulk is at the discussion table, yet the films psychological inquiries are more instinctively exploratory than scientifically ponderous. A reliance on tight shots during dialectic exchanges emphasizes Hulk’s focus on the emotional over the physical, the framing (often shot simultaneously from two angles) used more to emphasize expression than to define spatial relationships, often pushing logical details out of frame to focus more prominently on the eyes or center of the face. Such exquisite compositions speak wonders; from a cut between Mrs. Banner and the young Bruce – one of the most wondrous mother/child communications in recent memory – to any number of climactic stare-downs or soul-soothing tableaus, Lee knowingly utilizes his actor’s eyes, as they are the windows to the soul.

Like Tim Burton’s Batman Returns, Hulk is a superhero movie only incidentally about superheroes, the visceral flights of fancy a mere manifestation of the core themes of parent/child conflicts and the resulting scarring. Like him or not, Lee knows his predecessors, Hulk’s indebtedness to the surreal drama of the 1930’s horror lexicon knowingly indicated by two shots – one of the Hulk, one of Bruce Banner – lifted from Whale’s Bride of Frankenstein and Dreyer’s Vampyr (not to mention Jennifer Connelly, channeling countless damsels from decades past with a new sense of modern feminine empowerment). If Burton’s film is the more accomplished of the two (and by a great deal at that), it’s because that auteur was more comfortably learned in his canvas. Lee’s most recurrent theme is that of characters rectifying their inner struggles with external demands, and Hulk is his work most intrinsically representative of these notions. The film almost matches the inner conflict of its titular character, intermittently bogged down even as it soars to seemingly impossible heights.

Rating: A-