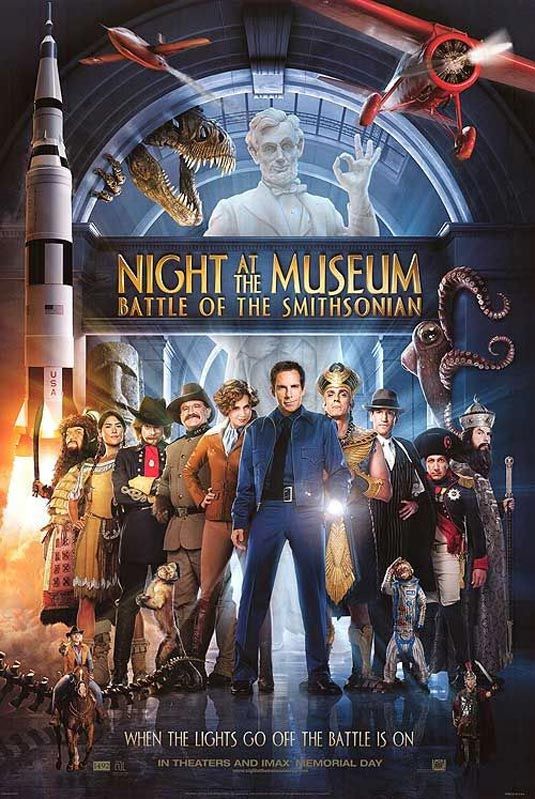

Back in 2006, I decided it would be wise to simply let the demographic at which Night at the Museum was aimed enjoy it, leaving my hat out of the proverbial ring. Having just endured the Happy Meal come-to-life sequel Battle of the Smithsonian, I now wish that I'd maintained that outlook. Shawn Levy reprises his directorial post in one of the most purely inept cinematic contraptions in recent memory, a parade of witless eye candy, weightless special effects and watered-down cultural references that threaten to make the Shrek sequels look desirable by comparison. Ben Stiller's Larry Daley has retired from his career as a night guard and now markets useless schlock pitched by George Foreman on early-morning informercials; a visit to his old stomping grounds reveals that the exhibits - which come to life whenever the sun goes down - are to be shipped out the following morning, permanently stored away and replaced by easier-to-maintain holograms. As a resurrected Amelia Earhart, the always-reliable Amy Adams is the lone saving grace to be found herein, which is a nice way of saying she's all that kept me from pondering "to be or not to be" during the film's contemptuous dumbing-down of every cultural corner it manages to lay its greedy hands on (which is to say nothing of its failure to establish anything in the way of basic spacial relationships or remotely believable timing in its action setpieces). From the revealingly inane decision to portray Al Capone in black and white to the should-have-been-hilarious-but-they-dropped-the-ball-anyway sequence involving Oscar the Grouch and Darth Vader to the inclusion of half the supporting cast from The Office, Battle of the Smithsonian isn't a movie even half as much as it is a feature-length advertising campaign for its idiotic self.

Back in 2006, I decided it would be wise to simply let the demographic at which Night at the Museum was aimed enjoy it, leaving my hat out of the proverbial ring. Having just endured the Happy Meal come-to-life sequel Battle of the Smithsonian, I now wish that I'd maintained that outlook. Shawn Levy reprises his directorial post in one of the most purely inept cinematic contraptions in recent memory, a parade of witless eye candy, weightless special effects and watered-down cultural references that threaten to make the Shrek sequels look desirable by comparison. Ben Stiller's Larry Daley has retired from his career as a night guard and now markets useless schlock pitched by George Foreman on early-morning informercials; a visit to his old stomping grounds reveals that the exhibits - which come to life whenever the sun goes down - are to be shipped out the following morning, permanently stored away and replaced by easier-to-maintain holograms. As a resurrected Amelia Earhart, the always-reliable Amy Adams is the lone saving grace to be found herein, which is a nice way of saying she's all that kept me from pondering "to be or not to be" during the film's contemptuous dumbing-down of every cultural corner it manages to lay its greedy hands on (which is to say nothing of its failure to establish anything in the way of basic spacial relationships or remotely believable timing in its action setpieces). From the revealingly inane decision to portray Al Capone in black and white to the should-have-been-hilarious-but-they-dropped-the-ball-anyway sequence involving Oscar the Grouch and Darth Vader to the inclusion of half the supporting cast from The Office, Battle of the Smithsonian isn't a movie even half as much as it is a feature-length advertising campaign for its idiotic self.

Dec 1, 2009

Night at the Museum: Battle of the Smithsonian (2009): D-

Back in 2006, I decided it would be wise to simply let the demographic at which Night at the Museum was aimed enjoy it, leaving my hat out of the proverbial ring. Having just endured the Happy Meal come-to-life sequel Battle of the Smithsonian, I now wish that I'd maintained that outlook. Shawn Levy reprises his directorial post in one of the most purely inept cinematic contraptions in recent memory, a parade of witless eye candy, weightless special effects and watered-down cultural references that threaten to make the Shrek sequels look desirable by comparison. Ben Stiller's Larry Daley has retired from his career as a night guard and now markets useless schlock pitched by George Foreman on early-morning informercials; a visit to his old stomping grounds reveals that the exhibits - which come to life whenever the sun goes down - are to be shipped out the following morning, permanently stored away and replaced by easier-to-maintain holograms. As a resurrected Amelia Earhart, the always-reliable Amy Adams is the lone saving grace to be found herein, which is a nice way of saying she's all that kept me from pondering "to be or not to be" during the film's contemptuous dumbing-down of every cultural corner it manages to lay its greedy hands on (which is to say nothing of its failure to establish anything in the way of basic spacial relationships or remotely believable timing in its action setpieces). From the revealingly inane decision to portray Al Capone in black and white to the should-have-been-hilarious-but-they-dropped-the-ball-anyway sequence involving Oscar the Grouch and Darth Vader to the inclusion of half the supporting cast from The Office, Battle of the Smithsonian isn't a movie even half as much as it is a feature-length advertising campaign for its idiotic self.

Back in 2006, I decided it would be wise to simply let the demographic at which Night at the Museum was aimed enjoy it, leaving my hat out of the proverbial ring. Having just endured the Happy Meal come-to-life sequel Battle of the Smithsonian, I now wish that I'd maintained that outlook. Shawn Levy reprises his directorial post in one of the most purely inept cinematic contraptions in recent memory, a parade of witless eye candy, weightless special effects and watered-down cultural references that threaten to make the Shrek sequels look desirable by comparison. Ben Stiller's Larry Daley has retired from his career as a night guard and now markets useless schlock pitched by George Foreman on early-morning informercials; a visit to his old stomping grounds reveals that the exhibits - which come to life whenever the sun goes down - are to be shipped out the following morning, permanently stored away and replaced by easier-to-maintain holograms. As a resurrected Amelia Earhart, the always-reliable Amy Adams is the lone saving grace to be found herein, which is a nice way of saying she's all that kept me from pondering "to be or not to be" during the film's contemptuous dumbing-down of every cultural corner it manages to lay its greedy hands on (which is to say nothing of its failure to establish anything in the way of basic spacial relationships or remotely believable timing in its action setpieces). From the revealingly inane decision to portray Al Capone in black and white to the should-have-been-hilarious-but-they-dropped-the-ball-anyway sequence involving Oscar the Grouch and Darth Vader to the inclusion of half the supporting cast from The Office, Battle of the Smithsonian isn't a movie even half as much as it is a feature-length advertising campaign for its idiotic self.

Nov 29, 2009

The Hangover (2009): C

The Hangover is a cheat, and not just because it's the latest, altogether lousy production to take the box office by unprecedented storm (already enough to reserve its status as one of the great overrated comedies of our era, and rest assured, this thing will only become more ungainly on DVD). Even viewed apart from its sterling reception, its disappointment stems from an inability to ever fully take off, like a airplane bolted to the runway. An amusing set-up - in which three friends (Bradley Cooper, Ed Helms and Zach Galifianakis) find themselves in the Nevada desert the morning after a bachelor party gone awry with the soon-to-be-married guest of honor nowhere to be found - ultimately goes all sorts of nowhere, the screenplay an overly and obviously scattershot attempt to cover as many broad humor bases as possible and one whose attempts at randomness instead bear the comparable spontaneity of a deliberately dropped anvil. With it, Todd Phillips cements his status as perhaps the most lethargically unironic comedy filmmaker working today (only the cheeky, self-reflexive Road Trip seems worth watching outside the walls of an alcohol-flooded frat house). Despite a few instances of legitimate comedic shock value (the end credits photo montage is an easy high water mark, albeit one that comes far too little too late), The Hangover stinks of committee production values; that the preview for the film is infinitely better than the final work says as much. Worse than its paint-by-numbers execution, however, is its total lack of empathy. Exclusively defining its characters via their non-femininity and non-homosexuality, the lack of scrutiny or definition given to their behavior slowly drowns the proceedings in a sludge of astonishingly obnoxious self-righteousness. You might call these guys flamingly straight, but you'd be just as well off saying they're unrepentant dicks. In a world with Superbad and I Love You, Man, The Hangover's witless regression is unforgivable.

The Hangover is a cheat, and not just because it's the latest, altogether lousy production to take the box office by unprecedented storm (already enough to reserve its status as one of the great overrated comedies of our era, and rest assured, this thing will only become more ungainly on DVD). Even viewed apart from its sterling reception, its disappointment stems from an inability to ever fully take off, like a airplane bolted to the runway. An amusing set-up - in which three friends (Bradley Cooper, Ed Helms and Zach Galifianakis) find themselves in the Nevada desert the morning after a bachelor party gone awry with the soon-to-be-married guest of honor nowhere to be found - ultimately goes all sorts of nowhere, the screenplay an overly and obviously scattershot attempt to cover as many broad humor bases as possible and one whose attempts at randomness instead bear the comparable spontaneity of a deliberately dropped anvil. With it, Todd Phillips cements his status as perhaps the most lethargically unironic comedy filmmaker working today (only the cheeky, self-reflexive Road Trip seems worth watching outside the walls of an alcohol-flooded frat house). Despite a few instances of legitimate comedic shock value (the end credits photo montage is an easy high water mark, albeit one that comes far too little too late), The Hangover stinks of committee production values; that the preview for the film is infinitely better than the final work says as much. Worse than its paint-by-numbers execution, however, is its total lack of empathy. Exclusively defining its characters via their non-femininity and non-homosexuality, the lack of scrutiny or definition given to their behavior slowly drowns the proceedings in a sludge of astonishingly obnoxious self-righteousness. You might call these guys flamingly straight, but you'd be just as well off saying they're unrepentant dicks. In a world with Superbad and I Love You, Man, The Hangover's witless regression is unforgivable.Nov 25, 2009

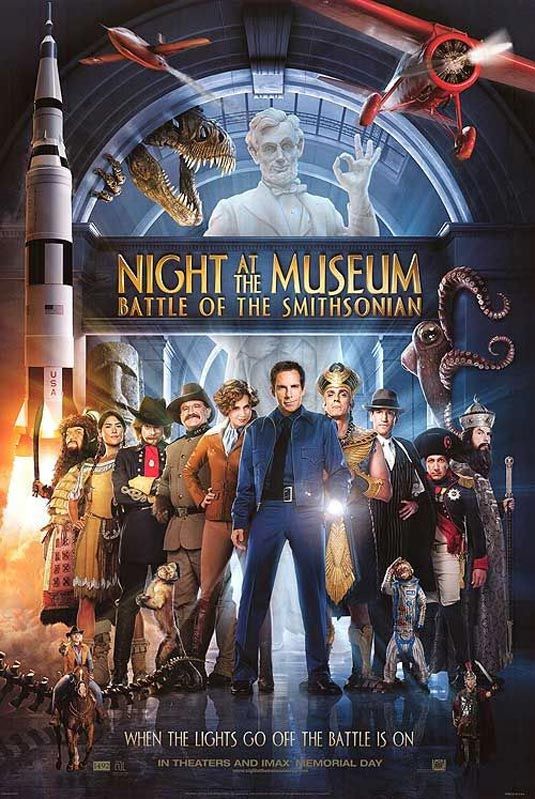

The Men Who Stare at Goats (2009): C

Seemingly intent on pleasing even those members of the audience who would otherwise be offended by its implicit lampooning of the American military complex, trademark wartime idiocy and all comparable areas of interest, The Men Who Stare At Goats comes to us as the latest political satire to have inadvertently sliced off its own pair. Concerning a military unit (the "New Army") developed post-Vietnam with the intention of creating psychic-enabled super-soldiers (referred to as Jedi Warriors, thus making the very decision to cast Ewan McGregor as the surrogate straight man some kind of desperate joke), the film follows McGregor's Bob Wilton as he decides to take his journalism career to Iraq during the dawn of the War on Terror, hoping to salvage his ego in the midst of an impromptu marital incineration. Fate, it would seem, brings him to Lyn Cassady (George Clooney), a New Army veteran traveling to Iraq for his own, often misleading, purposes. What follows is part road movie comedy, part new age existentialism with a forcibly ponderous tone that strikes all the wrong notes (the opening credits assure us that "more of this is true than you would believe", but even this seems less intent on actual enlightenment via humor than a mere conditioner for the detached, altogether "safe" black comedy to follow). A bit of research on the original book - unread by myself - suggests that whatever changes were made en route to the screen were surely for the worse. Either way, one must stand in a sort of awe at the skill it must have taken to waste the talents of Clooney, McGregor, Jeff Bridges and Kevin Spacey in the same film, let alone the same scene.

Seemingly intent on pleasing even those members of the audience who would otherwise be offended by its implicit lampooning of the American military complex, trademark wartime idiocy and all comparable areas of interest, The Men Who Stare At Goats comes to us as the latest political satire to have inadvertently sliced off its own pair. Concerning a military unit (the "New Army") developed post-Vietnam with the intention of creating psychic-enabled super-soldiers (referred to as Jedi Warriors, thus making the very decision to cast Ewan McGregor as the surrogate straight man some kind of desperate joke), the film follows McGregor's Bob Wilton as he decides to take his journalism career to Iraq during the dawn of the War on Terror, hoping to salvage his ego in the midst of an impromptu marital incineration. Fate, it would seem, brings him to Lyn Cassady (George Clooney), a New Army veteran traveling to Iraq for his own, often misleading, purposes. What follows is part road movie comedy, part new age existentialism with a forcibly ponderous tone that strikes all the wrong notes (the opening credits assure us that "more of this is true than you would believe", but even this seems less intent on actual enlightenment via humor than a mere conditioner for the detached, altogether "safe" black comedy to follow). A bit of research on the original book - unread by myself - suggests that whatever changes were made en route to the screen were surely for the worse. Either way, one must stand in a sort of awe at the skill it must have taken to waste the talents of Clooney, McGregor, Jeff Bridges and Kevin Spacey in the same film, let alone the same scene.

Nov 24, 2009

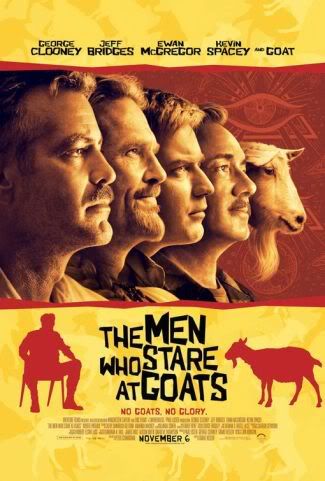

Law Abiding Citizen (2009): C-

While preferably to the typical Saw entry by about a five-to-one ratio, Law Abiding Citizen still isn't any good. Drab and borderline lethargic from virtually any cinematic standpoint (only the climactic image, which involves a character in a locked cell, offers something in the way of lyrical creativity), the most fascinating aspect of this modest train wreck is that anyone decided to give so embarrassingly nonsensical a script the green light. At the outset, Clyde Shelton (Gerard Butler) is the titular character: a loving husband and father who, after the tragic murder of his family, can only find comfort in the thought that the guilty will receive their due punishment at the hands of the state. Alas, when D.A. Nick Rice (Jamie Foxx) strikes a deal with the assailant in exchange for testimony on a much bigger fish, Shelton snaps and spends the next handful of years planning his revenge. So commences a string of murders beginning with the systematic torture and dismemberment of the sicko who killed Shelton's family, the intended and heavy-handed lesson being that the constitutional rights of known (but not convicted) killers should be seen as subservient to the lives of the innocent still in harm's way, with Shelton ultimately offering himself up for theoretical sacrifice in something of an inversion to Seven's harrowing climax. Even without taking into consideration the relatively black and white outlook on justice herein, Law Abiding Citizen is about the last argument one would want to seriously represent such a cause; as a moral thesis, it amounts to little more than heavy-lifting lip service, while the flaunting of so much purported violence (Shelton sends a videotape of the aforementioned dismemberment to Rice's home, etc.) confirms the film's interest in physical brutality over moral scrutiny. Seemingly able to orchestrate violent events from behind bars in a blatant manipulation of the legal system (made only to subsequently call out its flaws), Shelton's serpentine plot against the government is only sparsely made believable; at least Christopher Nolan's Joker seemed capable of pulling all the strings necessary to put the squeeze on an entire city, even if the particulars were never laid out in the open. As braindead entertainment, Citizen proves to be camp of the inadvertent kind; as philosophy, it's pure mistrial.

While preferably to the typical Saw entry by about a five-to-one ratio, Law Abiding Citizen still isn't any good. Drab and borderline lethargic from virtually any cinematic standpoint (only the climactic image, which involves a character in a locked cell, offers something in the way of lyrical creativity), the most fascinating aspect of this modest train wreck is that anyone decided to give so embarrassingly nonsensical a script the green light. At the outset, Clyde Shelton (Gerard Butler) is the titular character: a loving husband and father who, after the tragic murder of his family, can only find comfort in the thought that the guilty will receive their due punishment at the hands of the state. Alas, when D.A. Nick Rice (Jamie Foxx) strikes a deal with the assailant in exchange for testimony on a much bigger fish, Shelton snaps and spends the next handful of years planning his revenge. So commences a string of murders beginning with the systematic torture and dismemberment of the sicko who killed Shelton's family, the intended and heavy-handed lesson being that the constitutional rights of known (but not convicted) killers should be seen as subservient to the lives of the innocent still in harm's way, with Shelton ultimately offering himself up for theoretical sacrifice in something of an inversion to Seven's harrowing climax. Even without taking into consideration the relatively black and white outlook on justice herein, Law Abiding Citizen is about the last argument one would want to seriously represent such a cause; as a moral thesis, it amounts to little more than heavy-lifting lip service, while the flaunting of so much purported violence (Shelton sends a videotape of the aforementioned dismemberment to Rice's home, etc.) confirms the film's interest in physical brutality over moral scrutiny. Seemingly able to orchestrate violent events from behind bars in a blatant manipulation of the legal system (made only to subsequently call out its flaws), Shelton's serpentine plot against the government is only sparsely made believable; at least Christopher Nolan's Joker seemed capable of pulling all the strings necessary to put the squeeze on an entire city, even if the particulars were never laid out in the open. As braindead entertainment, Citizen proves to be camp of the inadvertent kind; as philosophy, it's pure mistrial.

Nov 23, 2009

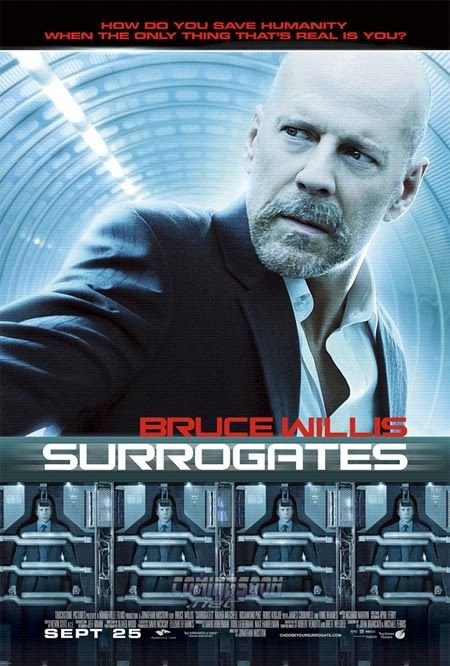

Surrogates (2009): A-

Star Trek might be the year's sci-fi rage, and while a fine space opera it may be, that it holds the upper hand amidst the competition only highlights how the exquisite work of Jonothan Mostow seems fated to go unappreciated in its time. With the WWII fable U-571 the only blemish on his resume (and that particular film's only flaw being the fact that it isn't great), his genre craftsmanship - while never as rapturously perfect as his predecessors (John Carpenter, James Cameron, Blade Runner-era Ridley Scott) - is nevertheless far and away from the typical studio worker. Surrogates joins Spielberg's sci-fi contributions and Michael Winterbottom's Code 46 as one of the defining dystopic visions of the decade, eschewing special effects glamour for a well-worn world in which the decidedly alien is an accepted given. The deliberate banality employed in the presentation of progressive robotic technologies renders the scenario with exponentially greater moral scrutiny and, concurrently, a creepy disconnection from human reality. As unfolds via an opening newsreel montage, the near future holds for us the development and mass social acceptance of surrogates: synthetic, humanoid robots used by the populace for their daily goings-on while their living flesh-and-blood selves pilot them from home; small groups of naturalist humans have quartered themselves off from the larger world and maintain an uneasy peace treaty (the plot centers around a terrorist weapon capable of destroying a surrogate in such a way that the host, too, is terminated; unlike those plugged into The Matrix, these things are supposed to be safeguarded here). Mostow's big budget B-movie draws exquisite everyman performances from the cast (in addition to eerie, necessarily artless performances as their characters' respective surrogates); Bruce Willis, as a cop not entirely unlike Blade Runner's Harrison Ford, is as flesh-and-blood empathetic as any role he's helmed since Die Hard. Scaled as if to suggest a budget even smaller than the actual, Surrogates seems less like a 21st Century would-be blockbuster than a lost 80's relic only just rediscovered. Either way, we're lucky to have it.

Star Trek might be the year's sci-fi rage, and while a fine space opera it may be, that it holds the upper hand amidst the competition only highlights how the exquisite work of Jonothan Mostow seems fated to go unappreciated in its time. With the WWII fable U-571 the only blemish on his resume (and that particular film's only flaw being the fact that it isn't great), his genre craftsmanship - while never as rapturously perfect as his predecessors (John Carpenter, James Cameron, Blade Runner-era Ridley Scott) - is nevertheless far and away from the typical studio worker. Surrogates joins Spielberg's sci-fi contributions and Michael Winterbottom's Code 46 as one of the defining dystopic visions of the decade, eschewing special effects glamour for a well-worn world in which the decidedly alien is an accepted given. The deliberate banality employed in the presentation of progressive robotic technologies renders the scenario with exponentially greater moral scrutiny and, concurrently, a creepy disconnection from human reality. As unfolds via an opening newsreel montage, the near future holds for us the development and mass social acceptance of surrogates: synthetic, humanoid robots used by the populace for their daily goings-on while their living flesh-and-blood selves pilot them from home; small groups of naturalist humans have quartered themselves off from the larger world and maintain an uneasy peace treaty (the plot centers around a terrorist weapon capable of destroying a surrogate in such a way that the host, too, is terminated; unlike those plugged into The Matrix, these things are supposed to be safeguarded here). Mostow's big budget B-movie draws exquisite everyman performances from the cast (in addition to eerie, necessarily artless performances as their characters' respective surrogates); Bruce Willis, as a cop not entirely unlike Blade Runner's Harrison Ford, is as flesh-and-blood empathetic as any role he's helmed since Die Hard. Scaled as if to suggest a budget even smaller than the actual, Surrogates seems less like a 21st Century would-be blockbuster than a lost 80's relic only just rediscovered. Either way, we're lucky to have it.

Oct 18, 2009

Halloween II (2009): B

The good news about Rob Zombie’s Halloween II (a sequel to the remake, not a remake of the sequel) is that it amplifies the strengths of its predecessor, a film I lightly panned upon first release, but have since come to appreciate more despite its shortcomings. The bad news, then, is that those shortcomings have also been amplified. Like the original Halloween II, Zombie’s film picks up the torch just after the conclusion of its predecessors October 31st bloodbath, here to detail the escape of the Michael Myers as his seemingly deceased body is transported from the scene of the crime. Approximately one year later, Laurie (Michael’s little sister, still unaware of her familial roots) is still trying to cope with the loss of her adoptive parents, while Dr. Loomis (Malcolm McDowell) is distastefully promoting his published account of the Myers killings. As the monstrously sized Myers (Tyler Mane) continues to leave a trial of human destruction, these two threads find themselves on a collision course that culminates on (you guessed it) Halloween night. First, the good: this film might be the most artfully rendered slasher sequel ever made, each slaughter portrayed with a revelatory intensity that suggests far more carnage than is shown outright, the jagged camerawork and muddled visuals evoking an existential meeting between predator and prey. As one overzealous fan of Dr. Loomis states it, Myers "eats at the core of the victims soul”.

The good news about Rob Zombie’s Halloween II (a sequel to the remake, not a remake of the sequel) is that it amplifies the strengths of its predecessor, a film I lightly panned upon first release, but have since come to appreciate more despite its shortcomings. The bad news, then, is that those shortcomings have also been amplified. Like the original Halloween II, Zombie’s film picks up the torch just after the conclusion of its predecessors October 31st bloodbath, here to detail the escape of the Michael Myers as his seemingly deceased body is transported from the scene of the crime. Approximately one year later, Laurie (Michael’s little sister, still unaware of her familial roots) is still trying to cope with the loss of her adoptive parents, while Dr. Loomis (Malcolm McDowell) is distastefully promoting his published account of the Myers killings. As the monstrously sized Myers (Tyler Mane) continues to leave a trial of human destruction, these two threads find themselves on a collision course that culminates on (you guessed it) Halloween night. First, the good: this film might be the most artfully rendered slasher sequel ever made, each slaughter portrayed with a revelatory intensity that suggests far more carnage than is shown outright, the jagged camerawork and muddled visuals evoking an existential meeting between predator and prey. As one overzealous fan of Dr. Loomis states it, Myers "eats at the core of the victims soul”.Alas, Zombie’s dark poetry only goes so far without more substantive justification, as the dreamlike images of Myer’s mother (Sheri Moon Zombie) and his childhood self (Chase Wright Vanek, replacing Daeg Faerch) don’t pry deeper into his pitiless, carnivorous psyche so much as they flaunt said perversions (a ravishing sequence shot in the vein of silent-era German expressionism ultimately proves the tip of a nonexistent psychological iceberg). Similarly unsubstantiated is the subplot of Loomis’ controversial book, which has garnered him death threats for the purported exploitation of Myers victims (of which Loomis had already nearly joined the ranks); save for the doctor’s own course personality and the flaunted gullibility of a media-saturated audience, this narrative thread ceases exploration at the surface level. Maybe that’s the point – that we’re droll cattle unwittingly lining up for the slaughter – but even if one is to embrace it from so nihilistic a standpoint doesn’t better the flat execution (all potential for satire croaks upon the utterance of an Austin Powers riff that’s been gathering dust for over a decade). The emotional anchor provided by the always-great Brad Dourif proves something of a saving grace during the final act, but it's not enough to correct the entirety of the preceding aimlessness. Let’s hope that Zombie’s next project cuts the filler and jettisons him back to Devil’s Rejects levels of greatness.

Oct 17, 2009

Dead Snow (2009): B

With the possible exception of Planet Terror, Dead Snow might be the dorkiest zombie film ever made, and I say that in praise. While the pre-credits opening – a hilariously self-aware, subversive chase scene scored to “In the Hall of the Mountain King” – stands as an easy comedic high point, that the rest of the movie holds up in comparison further underscores the overall stability and sly invention of the genre-riffing glee that is to follow. One of the few existing members of the Nazi zombie subgenre, this otherwise traditional tale revels in both the archetypal and schematic even as its violent means of dispatching both villains and protagonists proves more unpredictable than not. A group of medical students – played by an able cast, wisely straight-faced against the surrounding absurdity – finds themselves under attack during a weekend getaway at an isolated cabin deep in the snow covered mountains of Norway. Though well-equipped with movie-centric knowledge on how to survive such a confrontation – provided via a cinephiliac character whose T-shirt of choice proves an ominous bit of foreshadowing (all that’s missing is a baby) – they prove too heavily outnumbered by the squadron of the undead (which still operates according to rank, a humorous touch sadly not maximized to further effect) to simply stay put. Modestly ambitious and highly successfully within its chosen territory, Dead Snow proves to be one of the punchiest horror flicks in recent memory and one of the more capable within its low-budget constraints; the silent, lifeless landscapes make for a chilling tension-builder between each over-the-top set piece, while a memorable third-act shot of a character trapped beneath the snow is more nightmarishly claustrophobic than anything in The Descent. For the title of Best Zombie Comedy of 2009, Zombieland has a worthy competitor.

With the possible exception of Planet Terror, Dead Snow might be the dorkiest zombie film ever made, and I say that in praise. While the pre-credits opening – a hilariously self-aware, subversive chase scene scored to “In the Hall of the Mountain King” – stands as an easy comedic high point, that the rest of the movie holds up in comparison further underscores the overall stability and sly invention of the genre-riffing glee that is to follow. One of the few existing members of the Nazi zombie subgenre, this otherwise traditional tale revels in both the archetypal and schematic even as its violent means of dispatching both villains and protagonists proves more unpredictable than not. A group of medical students – played by an able cast, wisely straight-faced against the surrounding absurdity – finds themselves under attack during a weekend getaway at an isolated cabin deep in the snow covered mountains of Norway. Though well-equipped with movie-centric knowledge on how to survive such a confrontation – provided via a cinephiliac character whose T-shirt of choice proves an ominous bit of foreshadowing (all that’s missing is a baby) – they prove too heavily outnumbered by the squadron of the undead (which still operates according to rank, a humorous touch sadly not maximized to further effect) to simply stay put. Modestly ambitious and highly successfully within its chosen territory, Dead Snow proves to be one of the punchiest horror flicks in recent memory and one of the more capable within its low-budget constraints; the silent, lifeless landscapes make for a chilling tension-builder between each over-the-top set piece, while a memorable third-act shot of a character trapped beneath the snow is more nightmarishly claustrophobic than anything in The Descent. For the title of Best Zombie Comedy of 2009, Zombieland has a worthy competitor.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)