(This review concerns a 1925 silent, tinted version of the film that played on cable in the 1990s, a nearly exact version of which is embedded below.)

Indulge me for a moment of cinematic recollection (and a heads up for those who might object: if you’re reading this blog, then you already are). My very first viewing of any silent film – indeed, probably the first time that I even became aware of such a thing – was in my second grade music class, when we watched the original The Phantom of the Opera as a means of appreciating and understanding the role music played in enhancing movies. At the time, I was struck and absorbed by this incredible new form of storytelling, and became moderately obsessed with the film; fortunately for me, the Sci-Fi channel aired it not long after, the tape recording of which still resides in my extensive VHS library (as wondrous as DVD is, I have far too much invested in the old medium to entirely give it up).

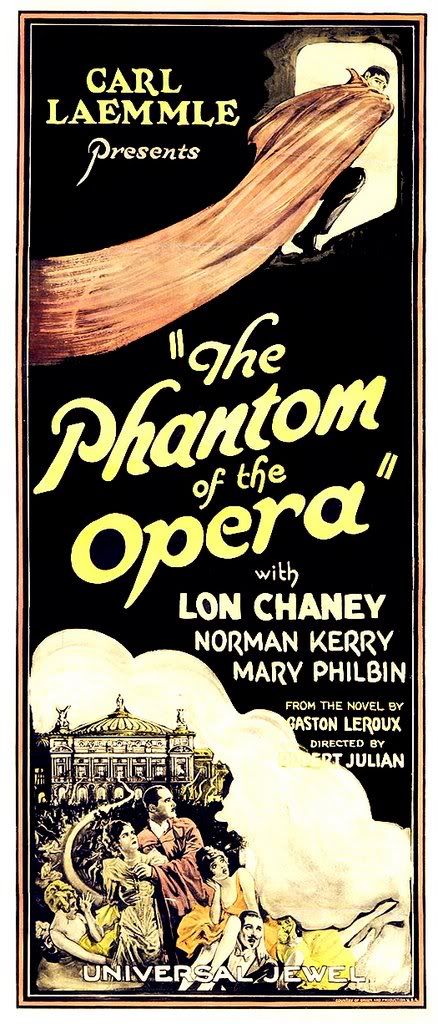

Unfortunately, revisiting Phantom – as both a cinematic hallmark and an object of nostalgic significance – finds the film’s reputation to far outrank its artistic quality (nevertheless, I pray it retains the oft-used “definitive” title even in the midst of the rancid 2004 Andrew Lloyd Webbed adaptation). Less a horror film than it is a more traditional melodrama, the film is annoyingly over-reliant on title cards (perhaps as a compensation for the generally lousy acting, or just poor direction in general) and underwhelming in its loose yet overcooked drama. The majority of the narrative weight is rested upon the underdeveloped love triangle at the center of the plotting. Christine (Mary Philbin) is an up-and-coming opera singer in France, her career aided by the mysterious Phantom (his identity unbeknownst to her) of the opera house, a legendary figure who resides in the basement levels, long corridors and old torture chambers long forgotten. Her lover and fiancée, Raoul (Norman Kerry), must be out of the picture in order for the Phantom to execute his long awaited plans.

The general story of the film, white admittedly a familiar one in its generalities, underwhelms; Christine and Raoul’s characters are reduced to such meandering talking heads that – even with great intent in doing so – emotional investment proves near impossible. That Phantom, one of the first of Universal Studio’s long-running horror genre (preceded only by the 1923 version of The Hunchback of Notre Dame), largely forged the blueprint for many of the films to follow it is a telling trait, for Phantom largely deals in formulas itself, the silent equivalent of a movie made not by an artist with a vision but a committee with dollar signs in their eyes. The haphazard production suggests enough: first filmed in 1924, Phantom was screened to poor results; re-shoots and multiple edits followed suit. Two official major prints now exist, the 1925 release and a 1929 re-release partially edited from alternate takes (the former being in question here). Plot holes abound (since none of the film is considered to be “lost,” this can be chalked up to poor craftsmanship rather than shoddy film preservation) and inexplicable tonal shifts further create a sense of divide (particularly the handful of silly and ineffective attempts at comic relief). While the film was a success upon its original release, that doesn’t change the fact that much of it feels like random piecemeal, which is to say that while many chunks of the film are indeed effective (and several downright terrifying), the overall effect is bipolar.

Amidst all the rough terrain, however, one unwaveringly fantastic element – that of Lon Chaney’s magnificent performance as the titular figure – rises to the surface. Even beneath the layers of self-applied, hideous makeup (which amount to one of the most memorable personas in film history), Chaney’s expressive presence and soulful body language help to fill in the twisted humanity of a character sorely undervalued by the film in which it exists. The Phantom, like everyone else, is but a chess piece moved about the shoddy narrative architecture, but even amidst bewildering moments of motivational inconsistency in the writing, Chaney instills a tremendous presence of soulful aching. The Phantom is an unrivaled maniac, professing of love and good intentions but ultimately an impossible mixture of greed, fear and piteous affection when things don’t turn out his way, the tormented product of a horrific life we desperately wish we could learn more of. Chaney’s Phantom stands out as a greater work within a lesser one, his gnarled form and sunken facial features commanded all attention whenever on screen (along with the shots of the opera’s underground labyrinths and a colorized sequence, they are among the only visually invigorating scenes in the film), leaving a chilling effect with each horrific expression. While the Phantom’s unmasking might be the most famous sequence in this lesser classic, none is more worthwhile for my money’s worth than the Phantom’s slow descent into a black, underground river, oxygen-providing reed in hand, ready to dispose of an unwanted visitor. Were the entire film so easily terrifying, then The Blair Witch Project would be given a deserved run for its money.

Indulge me for a moment of cinematic recollection (and a heads up for those who might object: if you’re reading this blog, then you already are). My very first viewing of any silent film – indeed, probably the first time that I even became aware of such a thing – was in my second grade music class, when we watched the original The Phantom of the Opera as a means of appreciating and understanding the role music played in enhancing movies. At the time, I was struck and absorbed by this incredible new form of storytelling, and became moderately obsessed with the film; fortunately for me, the Sci-Fi channel aired it not long after, the tape recording of which still resides in my extensive VHS library (as wondrous as DVD is, I have far too much invested in the old medium to entirely give it up).

Unfortunately, revisiting Phantom – as both a cinematic hallmark and an object of nostalgic significance – finds the film’s reputation to far outrank its artistic quality (nevertheless, I pray it retains the oft-used “definitive” title even in the midst of the rancid 2004 Andrew Lloyd Webbed adaptation). Less a horror film than it is a more traditional melodrama, the film is annoyingly over-reliant on title cards (perhaps as a compensation for the generally lousy acting, or just poor direction in general) and underwhelming in its loose yet overcooked drama. The majority of the narrative weight is rested upon the underdeveloped love triangle at the center of the plotting. Christine (Mary Philbin) is an up-and-coming opera singer in France, her career aided by the mysterious Phantom (his identity unbeknownst to her) of the opera house, a legendary figure who resides in the basement levels, long corridors and old torture chambers long forgotten. Her lover and fiancée, Raoul (Norman Kerry), must be out of the picture in order for the Phantom to execute his long awaited plans.

The general story of the film, white admittedly a familiar one in its generalities, underwhelms; Christine and Raoul’s characters are reduced to such meandering talking heads that – even with great intent in doing so – emotional investment proves near impossible. That Phantom, one of the first of Universal Studio’s long-running horror genre (preceded only by the 1923 version of The Hunchback of Notre Dame), largely forged the blueprint for many of the films to follow it is a telling trait, for Phantom largely deals in formulas itself, the silent equivalent of a movie made not by an artist with a vision but a committee with dollar signs in their eyes. The haphazard production suggests enough: first filmed in 1924, Phantom was screened to poor results; re-shoots and multiple edits followed suit. Two official major prints now exist, the 1925 release and a 1929 re-release partially edited from alternate takes (the former being in question here). Plot holes abound (since none of the film is considered to be “lost,” this can be chalked up to poor craftsmanship rather than shoddy film preservation) and inexplicable tonal shifts further create a sense of divide (particularly the handful of silly and ineffective attempts at comic relief). While the film was a success upon its original release, that doesn’t change the fact that much of it feels like random piecemeal, which is to say that while many chunks of the film are indeed effective (and several downright terrifying), the overall effect is bipolar.

Amidst all the rough terrain, however, one unwaveringly fantastic element – that of Lon Chaney’s magnificent performance as the titular figure – rises to the surface. Even beneath the layers of self-applied, hideous makeup (which amount to one of the most memorable personas in film history), Chaney’s expressive presence and soulful body language help to fill in the twisted humanity of a character sorely undervalued by the film in which it exists. The Phantom, like everyone else, is but a chess piece moved about the shoddy narrative architecture, but even amidst bewildering moments of motivational inconsistency in the writing, Chaney instills a tremendous presence of soulful aching. The Phantom is an unrivaled maniac, professing of love and good intentions but ultimately an impossible mixture of greed, fear and piteous affection when things don’t turn out his way, the tormented product of a horrific life we desperately wish we could learn more of. Chaney’s Phantom stands out as a greater work within a lesser one, his gnarled form and sunken facial features commanded all attention whenever on screen (along with the shots of the opera’s underground labyrinths and a colorized sequence, they are among the only visually invigorating scenes in the film), leaving a chilling effect with each horrific expression. While the Phantom’s unmasking might be the most famous sequence in this lesser classic, none is more worthwhile for my money’s worth than the Phantom’s slow descent into a black, underground river, oxygen-providing reed in hand, ready to dispose of an unwanted visitor. Were the entire film so easily terrifying, then The Blair Witch Project would be given a deserved run for its money.

No comments:

Post a Comment