Someone might say that 2001 is a bad film because of its lack of dialogue much in the same way a still-illiterate child will often prefer a picture book to the text of a written story. Traditional storytelling – wonderful as it can be in the right hands – has become, for many, not a single form but an absolute template, with off-kilter approaches often judged not by their own standards but by those most familiar to popular taste. It is in this way that a film like Kubrick’s masterpiece finds transcendence through its own pure manifestation – amidst its visual explorations, words would only get in the way, and unsurprisingly, it is often children who understand the film most fully, having not yet been desensitized to the narrative power of the image. Vice-versa, Sunshine is a technical marvel lacking the necessary conviction in its blistering vision of mortality – the film borderlines on masterpiece in its feverish sensory explosion, but is less than revelatory in its deliberate verbal exposition. This is misguided philosophy light, a life lesson unfairly bound to the confines of a vitamin capsule. That Boyle’s direction – like that of Alfonso Cuarón in Children of Men – is so good as to largely compensate for the unsatisfactory script is indeed a relief, but it also makes one long more for what could have been.

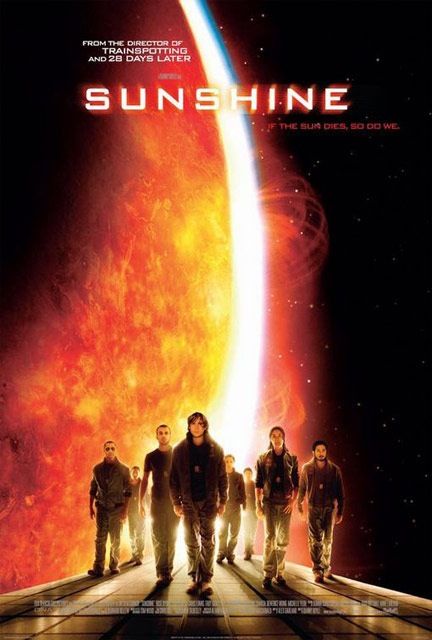

Someone might say that 2001 is a bad film because of its lack of dialogue much in the same way a still-illiterate child will often prefer a picture book to the text of a written story. Traditional storytelling – wonderful as it can be in the right hands – has become, for many, not a single form but an absolute template, with off-kilter approaches often judged not by their own standards but by those most familiar to popular taste. It is in this way that a film like Kubrick’s masterpiece finds transcendence through its own pure manifestation – amidst its visual explorations, words would only get in the way, and unsurprisingly, it is often children who understand the film most fully, having not yet been desensitized to the narrative power of the image. Vice-versa, Sunshine is a technical marvel lacking the necessary conviction in its blistering vision of mortality – the film borderlines on masterpiece in its feverish sensory explosion, but is less than revelatory in its deliberate verbal exposition. This is misguided philosophy light, a life lesson unfairly bound to the confines of a vitamin capsule. That Boyle’s direction – like that of Alfonso Cuarón in Children of Men – is so good as to largely compensate for the unsatisfactory script is indeed a relief, but it also makes one long more for what could have been.Sunshine’s end-of-days tale is an obvious but effective one, harking back to the days of early cinematic and literary science fiction, aided with a modern technological edge. Against the predictions of common physics, the sun has speedily reached the end of its lifespan, its internal chemical reactions sputtering out, threatening to leave the earth in deathly darkness and cold. Sent to the center of a solar system with a bomb in stow meant to re-ignite the star’s life-giving energy, the crew of Icarus II is the final vestige for humanity, their predecessors assumed long dead after having disappeared during their mission years earlier. Their plight suggests the heavy metal counterpart to Kubrick’s classical evocation of man’s relative insignificance in the universe; nearly blinded, a crew member stares at awe into the fiery rays of the sun, the spacecraft’s special shields and windows subjecting them to only 3% of its overall intensity. Long years away from their earthly habitats have worn on them in all the expected psychological ways, while the incomprehensible responsibility on their shoulders has rendered them a bunch of basket cases waiting to happen.

Like many a great genre film, Sunshine’s best moments of insight come from the implicit values seen in its unfolding story; questions of murder, sacrifice, and survival unpretentiously incorporated into an action-driven series of unfortunate events. These are aggravatingly diminished by the film’s moderately overt philosophical awareness, though it is – fortunately – but a small crutch unnecessarily indulged in, the unneeded icing on a cake good enough to make working around the extra decorations a worthwhile effort. Boyle’s work lacks finer elegance but its feral bombast can hardly be dismissed, the diffused imagery often suggesting the fabric time and space disintegrating around our protagonists. This manifestation of godly power ultimately takes a backseat to a newfound villain during the film’s much-maligned third act, a development that – in this critic’s eyes – stands as a perfectly natural, albeit visceral, progression on the film’s themes of power and madness, further expounding on man’s weaknesses through the plight of his own self-destruction. Sunshine is no Zen master, but it makes you feel the extremes of existence – the isolation of space versus the unity of all things – in ways knowingly hinged on the tenuous impulses of life. Call it sci-fi yoga and enjoy it as an appetizer to Solaris.

No comments:

Post a Comment