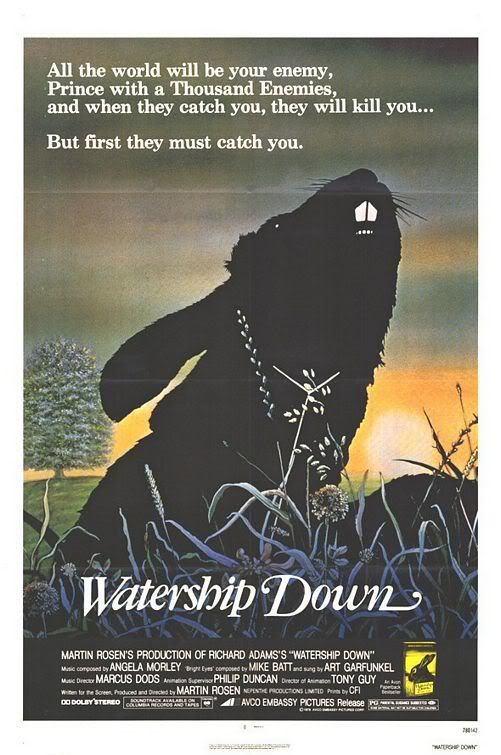

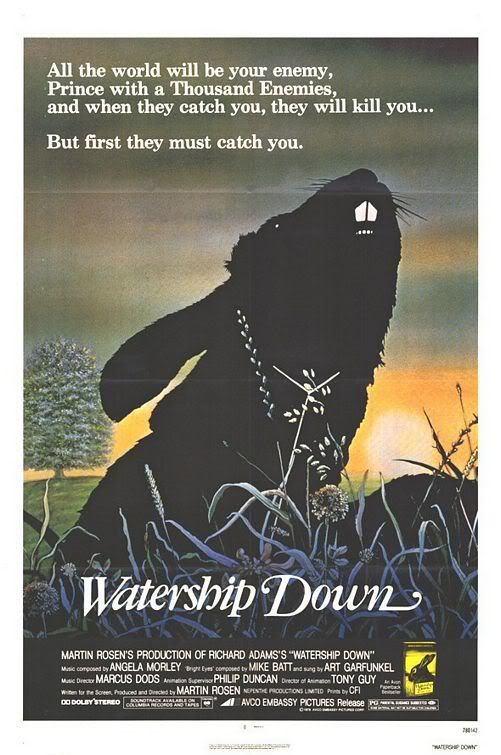

Don't let an apparently cute artifice fool you: Watership Down is the real deal, not unlike what Bambi might have been like if the death of the poor thing's mother had been stretched out to 90 minutes. Amidst a community of rabbits unknowingly in harm's immediate way—the plot of land they occupy having been targeted for construction by human destruction—one has a sudden, inexplicable uneasiness about oncoming danger, and urges the others to flee with him elsewhere. Many escape but some choose to stay (others are held by force), and thus begins this brilliantly animated film's tale of survival and camaraderie for the betterment of the whole. In actuality, the story is framed as a creation tale, the legend of the rabbit king who defied the gods, the purpose of whose very existence is to flee the thousand dangers of the world. The rabbits' interactions mirror those of human behavior (although the furry critters justly comment on our imperial, destructive relationship with the world), and so too does the film possess a startlingly tangible sense of death, from the blood that flows amidst gunshots and animal attacks to the petrifying black-out that accompanies one protagonist's suffocating trap in a wire snare. In searching for a new and safe home, the nomadic rabbits stumble upon another settlement, where the majority are ruled by an oppressive few bent on power. These verbally anthropomorphized bunnies talk with moving lips (like the "real" animals in the Babe films) but their threadbare nature of their illustrations keeps things effectively grounded in an earthly, natural tone, the fusion of hand drawn, unpolished sketches and inky watercolor work rendering the characters and their settings as real (thus fragile) and the simplicity of its necessarily black-and-white morality play (something of a non-human retelling of Sansho the Bailiff) even more potent. This honesty about the trials of life makes the film inarguably dark but the journey is always buoyant, focusing equally on the goodness therein as routinely embodied by the diverse and strongly personified characters: the courageous Hazel (an early John Hurt), the resilient (and stubborn) Bigwig (Michael Graham Cox), and a charmingly irate German seagull named Kehaar (the brilliant Zero Mostel's final film performance). I've not yet read the children's book of the same name by Richard Adams, but if it comes even close to Martin Rosen's film in terms of revolutionary life lessons, then it too is a necessary building block to the formulation of any child's aesthetic and moral taste.

Don't let an apparently cute artifice fool you: Watership Down is the real deal, not unlike what Bambi might have been like if the death of the poor thing's mother had been stretched out to 90 minutes. Amidst a community of rabbits unknowingly in harm's immediate way—the plot of land they occupy having been targeted for construction by human destruction—one has a sudden, inexplicable uneasiness about oncoming danger, and urges the others to flee with him elsewhere. Many escape but some choose to stay (others are held by force), and thus begins this brilliantly animated film's tale of survival and camaraderie for the betterment of the whole. In actuality, the story is framed as a creation tale, the legend of the rabbit king who defied the gods, the purpose of whose very existence is to flee the thousand dangers of the world. The rabbits' interactions mirror those of human behavior (although the furry critters justly comment on our imperial, destructive relationship with the world), and so too does the film possess a startlingly tangible sense of death, from the blood that flows amidst gunshots and animal attacks to the petrifying black-out that accompanies one protagonist's suffocating trap in a wire snare. In searching for a new and safe home, the nomadic rabbits stumble upon another settlement, where the majority are ruled by an oppressive few bent on power. These verbally anthropomorphized bunnies talk with moving lips (like the "real" animals in the Babe films) but their threadbare nature of their illustrations keeps things effectively grounded in an earthly, natural tone, the fusion of hand drawn, unpolished sketches and inky watercolor work rendering the characters and their settings as real (thus fragile) and the simplicity of its necessarily black-and-white morality play (something of a non-human retelling of Sansho the Bailiff) even more potent. This honesty about the trials of life makes the film inarguably dark but the journey is always buoyant, focusing equally on the goodness therein as routinely embodied by the diverse and strongly personified characters: the courageous Hazel (an early John Hurt), the resilient (and stubborn) Bigwig (Michael Graham Cox), and a charmingly irate German seagull named Kehaar (the brilliant Zero Mostel's final film performance). I've not yet read the children's book of the same name by Richard Adams, but if it comes even close to Martin Rosen's film in terms of revolutionary life lessons, then it too is a necessary building block to the formulation of any child's aesthetic and moral taste.Feb 25, 2008

Watership Down (1978): A-

Don't let an apparently cute artifice fool you: Watership Down is the real deal, not unlike what Bambi might have been like if the death of the poor thing's mother had been stretched out to 90 minutes. Amidst a community of rabbits unknowingly in harm's immediate way—the plot of land they occupy having been targeted for construction by human destruction—one has a sudden, inexplicable uneasiness about oncoming danger, and urges the others to flee with him elsewhere. Many escape but some choose to stay (others are held by force), and thus begins this brilliantly animated film's tale of survival and camaraderie for the betterment of the whole. In actuality, the story is framed as a creation tale, the legend of the rabbit king who defied the gods, the purpose of whose very existence is to flee the thousand dangers of the world. The rabbits' interactions mirror those of human behavior (although the furry critters justly comment on our imperial, destructive relationship with the world), and so too does the film possess a startlingly tangible sense of death, from the blood that flows amidst gunshots and animal attacks to the petrifying black-out that accompanies one protagonist's suffocating trap in a wire snare. In searching for a new and safe home, the nomadic rabbits stumble upon another settlement, where the majority are ruled by an oppressive few bent on power. These verbally anthropomorphized bunnies talk with moving lips (like the "real" animals in the Babe films) but their threadbare nature of their illustrations keeps things effectively grounded in an earthly, natural tone, the fusion of hand drawn, unpolished sketches and inky watercolor work rendering the characters and their settings as real (thus fragile) and the simplicity of its necessarily black-and-white morality play (something of a non-human retelling of Sansho the Bailiff) even more potent. This honesty about the trials of life makes the film inarguably dark but the journey is always buoyant, focusing equally on the goodness therein as routinely embodied by the diverse and strongly personified characters: the courageous Hazel (an early John Hurt), the resilient (and stubborn) Bigwig (Michael Graham Cox), and a charmingly irate German seagull named Kehaar (the brilliant Zero Mostel's final film performance). I've not yet read the children's book of the same name by Richard Adams, but if it comes even close to Martin Rosen's film in terms of revolutionary life lessons, then it too is a necessary building block to the formulation of any child's aesthetic and moral taste.

Don't let an apparently cute artifice fool you: Watership Down is the real deal, not unlike what Bambi might have been like if the death of the poor thing's mother had been stretched out to 90 minutes. Amidst a community of rabbits unknowingly in harm's immediate way—the plot of land they occupy having been targeted for construction by human destruction—one has a sudden, inexplicable uneasiness about oncoming danger, and urges the others to flee with him elsewhere. Many escape but some choose to stay (others are held by force), and thus begins this brilliantly animated film's tale of survival and camaraderie for the betterment of the whole. In actuality, the story is framed as a creation tale, the legend of the rabbit king who defied the gods, the purpose of whose very existence is to flee the thousand dangers of the world. The rabbits' interactions mirror those of human behavior (although the furry critters justly comment on our imperial, destructive relationship with the world), and so too does the film possess a startlingly tangible sense of death, from the blood that flows amidst gunshots and animal attacks to the petrifying black-out that accompanies one protagonist's suffocating trap in a wire snare. In searching for a new and safe home, the nomadic rabbits stumble upon another settlement, where the majority are ruled by an oppressive few bent on power. These verbally anthropomorphized bunnies talk with moving lips (like the "real" animals in the Babe films) but their threadbare nature of their illustrations keeps things effectively grounded in an earthly, natural tone, the fusion of hand drawn, unpolished sketches and inky watercolor work rendering the characters and their settings as real (thus fragile) and the simplicity of its necessarily black-and-white morality play (something of a non-human retelling of Sansho the Bailiff) even more potent. This honesty about the trials of life makes the film inarguably dark but the journey is always buoyant, focusing equally on the goodness therein as routinely embodied by the diverse and strongly personified characters: the courageous Hazel (an early John Hurt), the resilient (and stubborn) Bigwig (Michael Graham Cox), and a charmingly irate German seagull named Kehaar (the brilliant Zero Mostel's final film performance). I've not yet read the children's book of the same name by Richard Adams, but if it comes even close to Martin Rosen's film in terms of revolutionary life lessons, then it too is a necessary building block to the formulation of any child's aesthetic and moral taste.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Oh, you've got to read the book, although I wouldn't call it a "children's book" by any stretch what with the violence and death and nearly 500 pages (which, now that I think about it, in these post-Harry Potter days doesn't mean that it couldn't be a children's book). This is the only book I have re-read nearly every year for the last 25 years. I do remember seeing this movie version some time ago and they do a pretty faithful job of sticking to the source material; you're doing yourself a disservice though if you don't take the time to read it.

ReplyDeleteI wasn't wild about this movie when I saw it (I loved the book too), but it's one I wish they would remake. Today's animation would be perfect for it.

ReplyDeleteThe book is 1000 times better than the movie. There are nuances the movie just could not convey.

ReplyDeleteMany people believe this is a microcosm of the diaspora and genocide stories of mankind revisited by another species to take some of the sting.

In the book, you get a much better idea of how Fiver is the Moses figure, too.

to Craig:

ReplyDeleteI just don't see how 3D could do this story justice. People can appreciate the cuteness of 'Babe' but seem better able to accept darker themes with talking animals when done in traditional hand-drawn animation. Halas & Bachelor's 'Animal Farm' to me is still more effective than it's Jim Henson "live-action" remake.