There's one area in which you can't fault Michel Gondry's Be Kind Rewind, and that's in its esteemed and unwavering nostalgia for the video format alluded to in its fitting titular rhyme. Pity, then, that the video cassettes, like much else in this feature, are merely incidental elements in what amounts to the most traditional (read: predictable) narrative surrealistic wunderkind Michel Gondry has yet committed to the screen. After the conspiracy-obsessed Jerry (Jack Black) inadvertently destroys the entirety of a local video store's rental product, he and Mos Def's Mike (who is maintaining the store while Danny Glover's owner is away) must act fast to replace the antiquated products. Impending circumstances disallow them from doing the obvious (which would be replenishing their entire store product via eBay for about $10), and with the clock ticking they shoot and edit their own version of Ghostbusters for an important customer who's never seen the film before. Condensed moments such as these (Jack Black's interpretation of the Ghostbusters theme song has classic written all over it) instill the film with sporadic comedic brilliance, and while Gondry is no less assured in his tactics amidst such relatively normal material, his capabilities (and lack thereof) become apparent in this film's markedly different emotional tones. After Jerry and Mike's homemade movies become an unprecedented local hit (their reclusive New Jersey store drawing customers all the way from New York City), the cash starts rolling in like never before, but will it be enough to save the business in time? The bittersweet taste of the new paving over the old is indelible in the film's assessment of everything from how we consume our art to how we interpret history into our own lives, and Gondry understands the unifying power of creation that stands at the center of any community worth being a part of. Pity, then, that Be Kind Rewind ultimately trades in schmaltz of the unearned kind, laying it on so thick in the final act that it effectively smothers out the underdog virtues of its all-too endearing protagonists.

There's one area in which you can't fault Michel Gondry's Be Kind Rewind, and that's in its esteemed and unwavering nostalgia for the video format alluded to in its fitting titular rhyme. Pity, then, that the video cassettes, like much else in this feature, are merely incidental elements in what amounts to the most traditional (read: predictable) narrative surrealistic wunderkind Michel Gondry has yet committed to the screen. After the conspiracy-obsessed Jerry (Jack Black) inadvertently destroys the entirety of a local video store's rental product, he and Mos Def's Mike (who is maintaining the store while Danny Glover's owner is away) must act fast to replace the antiquated products. Impending circumstances disallow them from doing the obvious (which would be replenishing their entire store product via eBay for about $10), and with the clock ticking they shoot and edit their own version of Ghostbusters for an important customer who's never seen the film before. Condensed moments such as these (Jack Black's interpretation of the Ghostbusters theme song has classic written all over it) instill the film with sporadic comedic brilliance, and while Gondry is no less assured in his tactics amidst such relatively normal material, his capabilities (and lack thereof) become apparent in this film's markedly different emotional tones. After Jerry and Mike's homemade movies become an unprecedented local hit (their reclusive New Jersey store drawing customers all the way from New York City), the cash starts rolling in like never before, but will it be enough to save the business in time? The bittersweet taste of the new paving over the old is indelible in the film's assessment of everything from how we consume our art to how we interpret history into our own lives, and Gondry understands the unifying power of creation that stands at the center of any community worth being a part of. Pity, then, that Be Kind Rewind ultimately trades in schmaltz of the unearned kind, laying it on so thick in the final act that it effectively smothers out the underdog virtues of its all-too endearing protagonists.Feb 26, 2008

Be Kind Rewind (2007): B-

There's one area in which you can't fault Michel Gondry's Be Kind Rewind, and that's in its esteemed and unwavering nostalgia for the video format alluded to in its fitting titular rhyme. Pity, then, that the video cassettes, like much else in this feature, are merely incidental elements in what amounts to the most traditional (read: predictable) narrative surrealistic wunderkind Michel Gondry has yet committed to the screen. After the conspiracy-obsessed Jerry (Jack Black) inadvertently destroys the entirety of a local video store's rental product, he and Mos Def's Mike (who is maintaining the store while Danny Glover's owner is away) must act fast to replace the antiquated products. Impending circumstances disallow them from doing the obvious (which would be replenishing their entire store product via eBay for about $10), and with the clock ticking they shoot and edit their own version of Ghostbusters for an important customer who's never seen the film before. Condensed moments such as these (Jack Black's interpretation of the Ghostbusters theme song has classic written all over it) instill the film with sporadic comedic brilliance, and while Gondry is no less assured in his tactics amidst such relatively normal material, his capabilities (and lack thereof) become apparent in this film's markedly different emotional tones. After Jerry and Mike's homemade movies become an unprecedented local hit (their reclusive New Jersey store drawing customers all the way from New York City), the cash starts rolling in like never before, but will it be enough to save the business in time? The bittersweet taste of the new paving over the old is indelible in the film's assessment of everything from how we consume our art to how we interpret history into our own lives, and Gondry understands the unifying power of creation that stands at the center of any community worth being a part of. Pity, then, that Be Kind Rewind ultimately trades in schmaltz of the unearned kind, laying it on so thick in the final act that it effectively smothers out the underdog virtues of its all-too endearing protagonists.

There's one area in which you can't fault Michel Gondry's Be Kind Rewind, and that's in its esteemed and unwavering nostalgia for the video format alluded to in its fitting titular rhyme. Pity, then, that the video cassettes, like much else in this feature, are merely incidental elements in what amounts to the most traditional (read: predictable) narrative surrealistic wunderkind Michel Gondry has yet committed to the screen. After the conspiracy-obsessed Jerry (Jack Black) inadvertently destroys the entirety of a local video store's rental product, he and Mos Def's Mike (who is maintaining the store while Danny Glover's owner is away) must act fast to replace the antiquated products. Impending circumstances disallow them from doing the obvious (which would be replenishing their entire store product via eBay for about $10), and with the clock ticking they shoot and edit their own version of Ghostbusters for an important customer who's never seen the film before. Condensed moments such as these (Jack Black's interpretation of the Ghostbusters theme song has classic written all over it) instill the film with sporadic comedic brilliance, and while Gondry is no less assured in his tactics amidst such relatively normal material, his capabilities (and lack thereof) become apparent in this film's markedly different emotional tones. After Jerry and Mike's homemade movies become an unprecedented local hit (their reclusive New Jersey store drawing customers all the way from New York City), the cash starts rolling in like never before, but will it be enough to save the business in time? The bittersweet taste of the new paving over the old is indelible in the film's assessment of everything from how we consume our art to how we interpret history into our own lives, and Gondry understands the unifying power of creation that stands at the center of any community worth being a part of. Pity, then, that Be Kind Rewind ultimately trades in schmaltz of the unearned kind, laying it on so thick in the final act that it effectively smothers out the underdog virtues of its all-too endearing protagonists.Feb 25, 2008

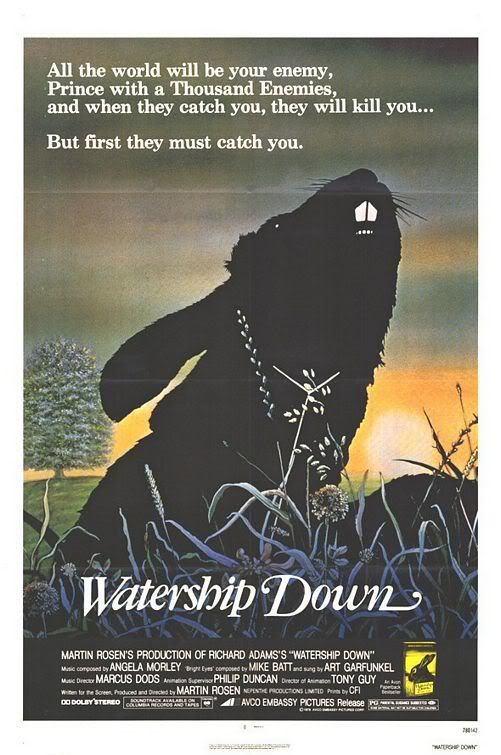

Watership Down (1978): A-

Don't let an apparently cute artifice fool you: Watership Down is the real deal, not unlike what Bambi might have been like if the death of the poor thing's mother had been stretched out to 90 minutes. Amidst a community of rabbits unknowingly in harm's immediate way—the plot of land they occupy having been targeted for construction by human destruction—one has a sudden, inexplicable uneasiness about oncoming danger, and urges the others to flee with him elsewhere. Many escape but some choose to stay (others are held by force), and thus begins this brilliantly animated film's tale of survival and camaraderie for the betterment of the whole. In actuality, the story is framed as a creation tale, the legend of the rabbit king who defied the gods, the purpose of whose very existence is to flee the thousand dangers of the world. The rabbits' interactions mirror those of human behavior (although the furry critters justly comment on our imperial, destructive relationship with the world), and so too does the film possess a startlingly tangible sense of death, from the blood that flows amidst gunshots and animal attacks to the petrifying black-out that accompanies one protagonist's suffocating trap in a wire snare. In searching for a new and safe home, the nomadic rabbits stumble upon another settlement, where the majority are ruled by an oppressive few bent on power. These verbally anthropomorphized bunnies talk with moving lips (like the "real" animals in the Babe films) but their threadbare nature of their illustrations keeps things effectively grounded in an earthly, natural tone, the fusion of hand drawn, unpolished sketches and inky watercolor work rendering the characters and their settings as real (thus fragile) and the simplicity of its necessarily black-and-white morality play (something of a non-human retelling of Sansho the Bailiff) even more potent. This honesty about the trials of life makes the film inarguably dark but the journey is always buoyant, focusing equally on the goodness therein as routinely embodied by the diverse and strongly personified characters: the courageous Hazel (an early John Hurt), the resilient (and stubborn) Bigwig (Michael Graham Cox), and a charmingly irate German seagull named Kehaar (the brilliant Zero Mostel's final film performance). I've not yet read the children's book of the same name by Richard Adams, but if it comes even close to Martin Rosen's film in terms of revolutionary life lessons, then it too is a necessary building block to the formulation of any child's aesthetic and moral taste.

Don't let an apparently cute artifice fool you: Watership Down is the real deal, not unlike what Bambi might have been like if the death of the poor thing's mother had been stretched out to 90 minutes. Amidst a community of rabbits unknowingly in harm's immediate way—the plot of land they occupy having been targeted for construction by human destruction—one has a sudden, inexplicable uneasiness about oncoming danger, and urges the others to flee with him elsewhere. Many escape but some choose to stay (others are held by force), and thus begins this brilliantly animated film's tale of survival and camaraderie for the betterment of the whole. In actuality, the story is framed as a creation tale, the legend of the rabbit king who defied the gods, the purpose of whose very existence is to flee the thousand dangers of the world. The rabbits' interactions mirror those of human behavior (although the furry critters justly comment on our imperial, destructive relationship with the world), and so too does the film possess a startlingly tangible sense of death, from the blood that flows amidst gunshots and animal attacks to the petrifying black-out that accompanies one protagonist's suffocating trap in a wire snare. In searching for a new and safe home, the nomadic rabbits stumble upon another settlement, where the majority are ruled by an oppressive few bent on power. These verbally anthropomorphized bunnies talk with moving lips (like the "real" animals in the Babe films) but their threadbare nature of their illustrations keeps things effectively grounded in an earthly, natural tone, the fusion of hand drawn, unpolished sketches and inky watercolor work rendering the characters and their settings as real (thus fragile) and the simplicity of its necessarily black-and-white morality play (something of a non-human retelling of Sansho the Bailiff) even more potent. This honesty about the trials of life makes the film inarguably dark but the journey is always buoyant, focusing equally on the goodness therein as routinely embodied by the diverse and strongly personified characters: the courageous Hazel (an early John Hurt), the resilient (and stubborn) Bigwig (Michael Graham Cox), and a charmingly irate German seagull named Kehaar (the brilliant Zero Mostel's final film performance). I've not yet read the children's book of the same name by Richard Adams, but if it comes even close to Martin Rosen's film in terms of revolutionary life lessons, then it too is a necessary building block to the formulation of any child's aesthetic and moral taste.The Brave Little Toaster (1987): A

Among the finest animated films Disney never made (but would like you to think they did), The Brave Little Toaster employs aesthetic simplicity to deliver an emotional wallop in its evocation of transformative childhood experiences—the dark, often unwanted discoveries that pave the way to a more enlightened adulthood. First made popular in Thomas M. Disch’s 1980 novel of the same name, the film presents its story of five common appliances—a toaster, an electric blanket, a vacuum cleaner, a lamp, and a radio—much like the intended bedtime narrative of its literary predecessor, at once fable-esque and genuinely hip. A lesser film might have smothered the beautiful stretches of scenery with some needless third-person voiceover, but Jerry Rees’ is one intimately reliant on often provocative, even disturbing imagery. When the five animated appliances decide to up and leave their abandoned cottage to search for their “master”—a young boy now grown and long departed from the summer home where our electrical protagonists now reside—one of their first discoveries is that of the surrounding wildlife, and in a life-impacting sequence, the toaster discovers a lone flower in the darkness of the wood. Unaccustomed to the mirror image before it, the flower relishes companionship before the toaster flees in fear, the lowly plant wilting soon thereafter in response to its now-assured solitude.

Among the finest animated films Disney never made (but would like you to think they did), The Brave Little Toaster employs aesthetic simplicity to deliver an emotional wallop in its evocation of transformative childhood experiences—the dark, often unwanted discoveries that pave the way to a more enlightened adulthood. First made popular in Thomas M. Disch’s 1980 novel of the same name, the film presents its story of five common appliances—a toaster, an electric blanket, a vacuum cleaner, a lamp, and a radio—much like the intended bedtime narrative of its literary predecessor, at once fable-esque and genuinely hip. A lesser film might have smothered the beautiful stretches of scenery with some needless third-person voiceover, but Jerry Rees’ is one intimately reliant on often provocative, even disturbing imagery. When the five animated appliances decide to up and leave their abandoned cottage to search for their “master”—a young boy now grown and long departed from the summer home where our electrical protagonists now reside—one of their first discoveries is that of the surrounding wildlife, and in a life-impacting sequence, the toaster discovers a lone flower in the darkness of the wood. Unaccustomed to the mirror image before it, the flower relishes companionship before the toaster flees in fear, the lowly plant wilting soon thereafter in response to its now-assured solitude.In many such ways does the film embitter its audience to the unfairness of the world, primarily for those who go about it with the best of intentions. Toaster’s titular qualities are relished most meaningfully in a decisive act of self-sacrifice, in a set piece pitting the appliances against what can be called the film's Great Satan, a literal hellmouth (a garbage dump trash compactor) that mercilessly destroys used cars and any other items deemed worthless by their former owners. The jazzy tune that accompanies said sequence plays both smoothly and deeply, the decrepit vehicles reminiscing days past with lyrics that shame nearly any production by the post-1960 Mouse House for pure existential weight (says a hearse, of all things: “I beg your pardon, it's quite hard enough / Just living with the stuff I have learned”).

This emotionally direct approach finds an appropriate outlet in the spare, bold animation style, though it is a choice that renders some of the dream sequences almost unintentionally hilarious in their surrealism. Such simplicity is a virtue Disney would only incidentally stumble upon some time later with their similarly excellent Lilo & Stitch, in which they deliberately held back on animation detail in response to diminishing box office returns for hand-drawn fare. Perhaps most affecting here, though, is the strong voice work, a key selling point when it comes to any successful case of anthropomorphization (see also Toy Story and Aqua Teen Hunger Force). The barely-exposed Deanna Oliver strikes a perfect line of gender ambiguity for the titular hero, while a pre-SNL Jon Lovitz lays out the groundwork for his Critic star Jay Sherman as a loudmouth, Roosevelt-obsessed (both Teddy and Franklin) clock radio. Ditto excellence for the rest of the cast (including Thurl Ravenscroft, best known as Frosted Flakes’ advertising icon Tony the Tiger), who render their characters as miniaturized archetypes working their way through the world. One can only imagine what would have been the case had the film’s initially proposed Disney production gone ahead, it’s $18 million budget slashed to just over $2 million when it was eventually outsourced to an independent company. Though a big hit at the 1988 Sundance Festival, the film was left distributor-less until Disney again picked it up for cable rights and a strong VHS release. Sporting only a brief run at New York’s Film Forum and other limited theatrical exposures, The Brave Little Toaster remains among the most criminally ignored works of the past twenty years. Though owner of distribution rights and responsible for two lesser sequels, when it comes to nostalgic childhood ruminations, Disney can’t touch this.

Feb 1, 2008

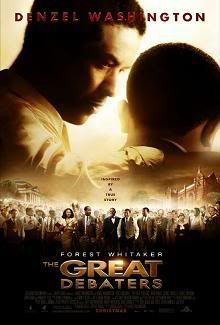

The Great Debaters (2007): C

The latest history lesson brought to you courtesy of Oprah Winfrey, The Great Debaters flails about in its attempts to portray both genuine human behavior as it exists at a historical crossroad as well as events meant to uplift, any sense of emotion or truth sapped dry from the proceedings by an all-encompassing sense of not only fatalistic obviousness, but also plain old lazy storytelling. This week's tutorial provides us with another example of How to Get the Man's Foot Outta Your Ass, focusing on the 1935 African-American Wiley College of Texas, whose tremendously successful debate team went on to debate Harvard University in an historic showdown of class and race, despite the expected opposition from bigots as well as the brouhaha that occurred following their teacher Mel Tolson's (Denzel Washington) blacklisting as a social activist. Director/star Washington waxes this homogenized account of history—seriously, lynching never felt so weightless as it is portrayed here—with bland competence, more intent on tried-and-true methods of obvious cut-and-paste storytelling than examining the complex social turmoil of the time in ways not easily summed up in quotable and over-written speeches ("The time for justice is always right now!"), sacrificing lived-in truth for compact moralizing. It isn't cinema so much as inane historical recreation given narrative form, its unveiling more akin to textbook notes than spontaneous human behavior (seriously, Killer of Sheep finally gets an official release and this is what gets nominated for awards?). As is typical of such fare, the primary goals are commendable for their well-intentioned earnestness, but zero points for such gluttonous condescension.

The latest history lesson brought to you courtesy of Oprah Winfrey, The Great Debaters flails about in its attempts to portray both genuine human behavior as it exists at a historical crossroad as well as events meant to uplift, any sense of emotion or truth sapped dry from the proceedings by an all-encompassing sense of not only fatalistic obviousness, but also plain old lazy storytelling. This week's tutorial provides us with another example of How to Get the Man's Foot Outta Your Ass, focusing on the 1935 African-American Wiley College of Texas, whose tremendously successful debate team went on to debate Harvard University in an historic showdown of class and race, despite the expected opposition from bigots as well as the brouhaha that occurred following their teacher Mel Tolson's (Denzel Washington) blacklisting as a social activist. Director/star Washington waxes this homogenized account of history—seriously, lynching never felt so weightless as it is portrayed here—with bland competence, more intent on tried-and-true methods of obvious cut-and-paste storytelling than examining the complex social turmoil of the time in ways not easily summed up in quotable and over-written speeches ("The time for justice is always right now!"), sacrificing lived-in truth for compact moralizing. It isn't cinema so much as inane historical recreation given narrative form, its unveiling more akin to textbook notes than spontaneous human behavior (seriously, Killer of Sheep finally gets an official release and this is what gets nominated for awards?). As is typical of such fare, the primary goals are commendable for their well-intentioned earnestness, but zero points for such gluttonous condescension.

The 4th Dimension (2006): B

A rundown of The 4th Dimension's stylistic traits would suggest little more than a hodgepodge of Polanski, Aronofsky, and Lynch, but the reality is that the debut of directorial team Tom Mattera and David Mazzoni—while obviously indebted to such cinematic forbearers—is an accomplished work indicative of a unique cinematic vision. Its title referring to the realm of existence in which time becomes a tangible element, the film exists mostly within the mental head space of its main character Jack Emitni (Louis Morabito), an OCD-stricken individual obsessed with the manipulation of time, emotionally paralyzed after suffering a devastating loss as a child. Although the film would seem to engage in some of the mumbo-gumbo philosophizing that passes for true existentialism in far too many works of art, The 4th Dimension prevails for both its overall lack of pretension, as well as a more implicit approach to such psychological mind games, verbal clarification taking a backseat to a mise en scène of eerie sights and sounds. Jack returns again and again to lost moments of his life much in the same way that he compulsively washes his hands, haunted by thoughts, memories, and a mysterious femme fatale with a timepiece in need of repair. Although the film isn't an unqualified success—Eraserhead this is not—its many virtues suggest that, were it for but a more flexible shooting budget, its core elements could have been embellished into something resembling a masterwork. Such as it is, the film's low-budget black and white look is a hit-and-miss affair, too often rendering its images flat, though while simultaneously achieving a handful of astounding, miniaturized power shots, contrasting blacks and whites with awesome precision and in the process creating a truly palpable sense of dread. The carefully placed use of wide shots, disembodied long takes and delectably framed close-ups suggest a presence well learned in style and substance, and while several of the single-take sequences would have benefited from a more loquacious pacing, there are enough awe-inspiring ones to signify a creative force to be reckoned with, transforming otherwise throwaway moments—the fetching of keys, the descent of a staircase, the approach to a secluded house—into epochs of haunted house madness. The remainder of the film's limitations, then—overly actor-y performances by some of the supporting cast and the occasionally repetitious visual metaphor—seem implicit with its homegrown indie roots. Given The 4th Dimension's numerous strengths, one can only hope that future efforts see the directors completely freeing themselves of such weighty narrative expectations.

A rundown of The 4th Dimension's stylistic traits would suggest little more than a hodgepodge of Polanski, Aronofsky, and Lynch, but the reality is that the debut of directorial team Tom Mattera and David Mazzoni—while obviously indebted to such cinematic forbearers—is an accomplished work indicative of a unique cinematic vision. Its title referring to the realm of existence in which time becomes a tangible element, the film exists mostly within the mental head space of its main character Jack Emitni (Louis Morabito), an OCD-stricken individual obsessed with the manipulation of time, emotionally paralyzed after suffering a devastating loss as a child. Although the film would seem to engage in some of the mumbo-gumbo philosophizing that passes for true existentialism in far too many works of art, The 4th Dimension prevails for both its overall lack of pretension, as well as a more implicit approach to such psychological mind games, verbal clarification taking a backseat to a mise en scène of eerie sights and sounds. Jack returns again and again to lost moments of his life much in the same way that he compulsively washes his hands, haunted by thoughts, memories, and a mysterious femme fatale with a timepiece in need of repair. Although the film isn't an unqualified success—Eraserhead this is not—its many virtues suggest that, were it for but a more flexible shooting budget, its core elements could have been embellished into something resembling a masterwork. Such as it is, the film's low-budget black and white look is a hit-and-miss affair, too often rendering its images flat, though while simultaneously achieving a handful of astounding, miniaturized power shots, contrasting blacks and whites with awesome precision and in the process creating a truly palpable sense of dread. The carefully placed use of wide shots, disembodied long takes and delectably framed close-ups suggest a presence well learned in style and substance, and while several of the single-take sequences would have benefited from a more loquacious pacing, there are enough awe-inspiring ones to signify a creative force to be reckoned with, transforming otherwise throwaway moments—the fetching of keys, the descent of a staircase, the approach to a secluded house—into epochs of haunted house madness. The remainder of the film's limitations, then—overly actor-y performances by some of the supporting cast and the occasionally repetitious visual metaphor—seem implicit with its homegrown indie roots. Given The 4th Dimension's numerous strengths, one can only hope that future efforts see the directors completely freeing themselves of such weighty narrative expectations.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)