Classics like

Dirty Harry make me wish that I’d been born earlier (in this case, to have been able to call it out from day one). Even if you’re able to look past its flimsy support of fascism (more on that later), this is frequently as sloppily constructed a genre film as those that are typical to today’s multiplexes. The film’s must-see benefit is its pivotal status in the ascent of Clint Eastwood to stardom, yet even as an isolated element, it’s hard to conceive that such an awkward performance ever came to hold such sway in the culture. Harry Callahan’s signature “Do you feel lucky?” line works neither as a roll-of-the-dice gamble (as initially suggested in the film’s early bank robbery shoot-out) or bitter menace (as we come to know it through repetition). Here, Eastwood lacks the sincerity of his character's purported grizzle, and his my-way-or-the-highway bravado comes off as cheap posturing in a film desperate to seem like the authority on justice or morality. Frankly, the guy’s an idiot (Callahan, not Eastwood), and so is any filmmaker that expects intelligent audiences to believe that a hard-boiled San Francisco officer would lack even a rudimentary understanding of American civil rights as pertaining to the acquisition of evidence – a inanity upon which the borderline propagandistic plot hinges. The central villain, who goes by the pseudo-ominous moniker Scorpio (Andrew Robinson), is a hilarious amalgamation of the 70s counterculture – good (sports a peace symbol), bad (deliberately gives cops a bad name) and ugly (rapist, sniper, kidnapper of children, etc.) – upon which viewers can project all their negative feelings about dem der longhair hippie sonovabitches. Dirty Harry (as Callahan is known, for always taking the ugliest of jobs) might embody some ultra-fascist fantasy, but the straw-man arguments made here skew towards caveman us-versus-them idiocy.

[C-]

Godzilla vs. Hedorah

Godzilla vs. Hedorah (aka

Godzilla vs. the Smog Monster) was always my least favorite of the numerous monster-mashing sequels as a child; rewatching it these years later, there’s something reassuring in having my then-budding tastes confirmed. Though more stylistically distinct than most of its counterparts – dabbling in 70s psychedelics, surreal animated divergences, and jazzy introductions for the titular lizard – this entry is also among the most lifeless of the series, a not insubstantial designation given the central conflict of two high-rise monsters duking it out with life on Earth as we know it hanging in the balance. The opening images of untold tons of garbage collected in the ocean sets an appropriately queasy tone; soon, multiple tadpole-like Hedorah monsters are born of the mineral waste, laying waste to ships at sea before merging together into a creature capable of coming ashore and, eventually, flight (the parallels to basic evolutionary theory are amusing, but, alas, go relatively untapped). Enter Godzilla to save the day, here cast as something of a wrestling icon; the glove, suffice to say, doesn’t fit, thanks in no small part to the lacking choreography on display. The image of the massive smog beast sucking fumes off of pollutant factory pipes proves almost indelible, but little else registers in this awkwardly overt forerunner to

An Inconvenient Truth’s cautionary environmental warnings.

[C-]

It especially pales in comparison to the similarly themed

Godzilla vs. Gigan (aka

Godzilla on Monster Island, released stateside in 1977), itself among the most efficient and exciting of the series since the 1954 original; in it, cockroach-like aliens attempt to wipe out humanity so as to clear the Earth for themselves, their home planet now a lifeless wasteland after years of abuse. Jun Fukuda’s imaginative set pieces dwarf the poorly staged, drawn-out confrontations between Godzilla and Hedorah; mounting tensions between the monsters and military have an almost musical rhythm, while the montages of assembling infantry (comprised of both real military vehicles and blatant model stand-ins) building up to the monster’s attack exemplify the childlike wonder implicit in the latter-day Godzilla. As a newcomer, Gigan isn’t as creatively conceived a villain as the film would have you think (outside of close encounters, the buzz-saw in his belly seems a remarkably useless weapon), and

Ghidorah has always struck me as somewhat flippant, with little to no apparent coordination or cooperation between the three heads. Nevertheless, such is of little consequence given Godzilla and the spiky Anguirus’ cheeky, one-two displays of badassitude. Inner eight-year-old, you may now commence having a blast.

[B+]

The Limits of Control

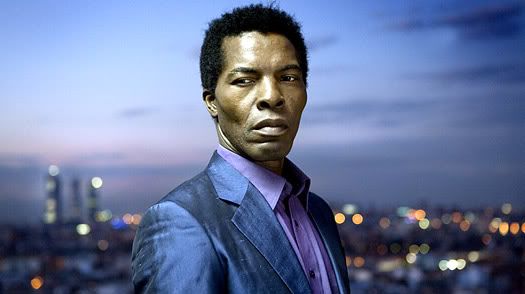

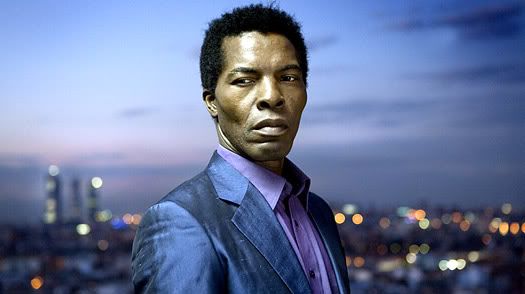

The Limits of Control may be the best movie I haven’t enjoyed in recent memory. Seen under just about the least ideal of circumstances, Jim Jarmusch’s polarizing exercise in stylized minimalism struck me as accomplished, intoxicating, and ultimately, infuriating; was it the film that got under my skin, or was it the horrendous day I’d been having? Had it been screening in any New York City theater besides the Angelika Film Center (a location at which, I feel confident in saying, there is no quality cinematic experience can be had by yours truly), I’d have resubmitted myself to it’s super-cool suave for another go around, but until the DVD release, I’m willing to give it the benefit of the doubt. Following the hyper-methodical activities of a character known only as Lone Man (Isaach De Bankolé),

The Limits of Control seems to exist neither in complete reality or complete fantasy, what with its own audio/visual signifiers occasionally spilling over the lines we rely on to define our realities. Many reviews spilled on plot details not actually revealed until well into the picture (thus, I found, diminishing the impact of their reveal), proving how few among our critical establishment can actually discern between those films in which hard story is primary versus secondary; perhaps more worryingly, how many even care to? Here, repetition takes on an ethereal quality, though I’m not entirely convinced that the oft-repeated philosophies and sound bytes work any better when taken as emotional manipulators instead of intellectual stimulators. More so than any 2009 release to date, I anxiously await a second viewing.

[B]