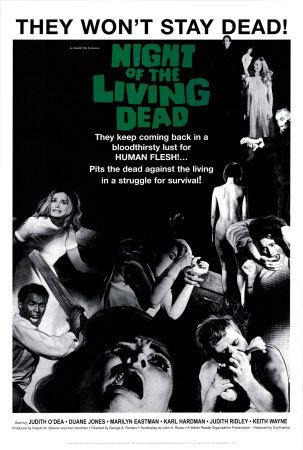

Fuck hyperbole – George A. Romero's debut film Night of the Living Dead may be the purest horror film ever made. Only the memories of those who were first there during its unveiling can attest to just how revolutionary a creation it was, simultaneously redefining the rules and capabilities of the medium while also forging an entirely new subgenre that – if the recent success of a third Resident Evil film and the upcoming remake of Romero's own sequel Day of the Dead are any indication – remains alive and well today (no pun intended). Even during my first, now hallowed viewing experience, I knew what the zombies were and the general "rules" surrounding them; the reactivation of the body via some viral infection or radiative force, the eating of the flesh of the living, the fact that those bitten by a zombie would ultimately become one themselves, and the killing of the undead through the destruction of the reanimated brain. These qualities have long since been absorbed into horror culture at the same level as Frankenstein and Dracula, the fact of which attests to Night of the Living Dead's timeless potency as one of the genre's most formidable exercises. Although among my most re-watched films, it never fails to evoke the same chills time and time again. Romero would go on to more brilliant and complex works, but in its own direct way, Night of the Living Dead represents unsurpassable perfection.

Kneading its murky imagery into a tsunami of terror over the course of an agonizing hour and a half, Night of the Living Dead focuses primarily on suggestion over action, the tangible violence and onscreen conflicts complimented by a foundation of perpetual, mysterious dread, of normality imploding on itself. A day trip to visit the grave of their father turns into a living hell for Barbra (Judith O'Dea) and her brother Johnny (Russell Streiner), who happen into the middle of the outbreaking zombie plague just as it begins, with any explanation for the sudden terror besieging them amounting to nil. Johnny taunts Barbara over her childhood fear of the cemetery, only for the wandering man in their midst to actually have been already "coming to get her" in the first place. Night may seem overeager to send shivers down its viewers spines but the film works precisely as a validation of our deepest childhood fears, from what we're unable to see in the dark to the general strangeness abound in much of our everyday bric-a-brac. Romero's minimalist cinematography borrows a page from Polanski in its diagonal framing, often suggesting an ethereal landscape of blacks and grays melding into each other, not unlike some dense fabric from which the monsters of our dreams come for us at our most vulnerable. The lack of visual distinction may be the film's most powerful attribute; like the splotchy paint strokes of a surrealist work, our imaginations work overtime to "fill in" the gaps, without our even realizing it.

Kneading its murky imagery into a tsunami of terror over the course of an agonizing hour and a half, Night of the Living Dead focuses primarily on suggestion over action, the tangible violence and onscreen conflicts complimented by a foundation of perpetual, mysterious dread, of normality imploding on itself. A day trip to visit the grave of their father turns into a living hell for Barbra (Judith O'Dea) and her brother Johnny (Russell Streiner), who happen into the middle of the outbreaking zombie plague just as it begins, with any explanation for the sudden terror besieging them amounting to nil. Johnny taunts Barbara over her childhood fear of the cemetery, only for the wandering man in their midst to actually have been already "coming to get her" in the first place. Night may seem overeager to send shivers down its viewers spines but the film works precisely as a validation of our deepest childhood fears, from what we're unable to see in the dark to the general strangeness abound in much of our everyday bric-a-brac. Romero's minimalist cinematography borrows a page from Polanski in its diagonal framing, often suggesting an ethereal landscape of blacks and grays melding into each other, not unlike some dense fabric from which the monsters of our dreams come for us at our most vulnerable. The lack of visual distinction may be the film's most powerful attribute; like the splotchy paint strokes of a surrealist work, our imaginations work overtime to "fill in" the gaps, without our even realizing it. Romero denies having intended any racial commentary in his character's power struggle, but it's actually the final series of unfortunate events that solidify the work as one of 60's activism rooted in social unease. Ben (Duane Jones) and Harry Cooper (Karl Hardman) duke it out not as black man and white man but as entangled might and pride, and it is in its observation of people interacting under the strains of unimaginable duress that Night of the Living Dead becomes most universal. It's downright impossible to not recall 9/11 as our human protagonists, safe for the time being in their boarded-up country house, huddle around a television waiting with baited breath for the next nugget of information about the unfolding chaos around them. Along with my virginity, I'd give damn near anything to watch the film again for the first time, totally ignorant not only of its own narrative progression but of all things zombie. Horror films have become more technically gruesome and forcefully shocking in the past forty years, and indeed, some have surpassed the film in scares, if not in aesthetic potency. No amount of technical nuance, however, could ever hope to rival Night's sinister lurk through the subconscious. From the subtle voyeurism of its opening credits through its impossibly bleak conclusion, it subjects us to the kind of unrelenting nightmare we only wish we could wake up from.

Romero denies having intended any racial commentary in his character's power struggle, but it's actually the final series of unfortunate events that solidify the work as one of 60's activism rooted in social unease. Ben (Duane Jones) and Harry Cooper (Karl Hardman) duke it out not as black man and white man but as entangled might and pride, and it is in its observation of people interacting under the strains of unimaginable duress that Night of the Living Dead becomes most universal. It's downright impossible to not recall 9/11 as our human protagonists, safe for the time being in their boarded-up country house, huddle around a television waiting with baited breath for the next nugget of information about the unfolding chaos around them. Along with my virginity, I'd give damn near anything to watch the film again for the first time, totally ignorant not only of its own narrative progression but of all things zombie. Horror films have become more technically gruesome and forcefully shocking in the past forty years, and indeed, some have surpassed the film in scares, if not in aesthetic potency. No amount of technical nuance, however, could ever hope to rival Night's sinister lurk through the subconscious. From the subtle voyeurism of its opening credits through its impossibly bleak conclusion, it subjects us to the kind of unrelenting nightmare we only wish we could wake up from.Feature: 31 Days of Zombie!

Thanks so much for this series, Rob! You've certainly pointed out a couple of undiscovered gems I intend to seek out over the coming months! I've enjoyed this series immensely!

ReplyDeleteChris

Great series!

ReplyDeleteBut be careful about your listing of the "rules" of zombie films -- specifically "the reactivation of the body via some viral infection or radiative force."

Wasn't half the point of Romero's films that we never really find out what's caused all this? It's really the lesser spawn of Romero that takes pains to explain, and thereby minimize the horror, of the whole zombie apocalypse experience.

(though to be fair, I'd have to re-view Night to check this, as I seem to recall some kind of hint -- but it was certainly never made clear the way the other rules, like "shoot 'em in the head!", were)

anonymous: Excellent point indeed. I should have made it clearer that these "rules" are the generally known ones, albeit subject to interpretations (such as "The Return of the Living Dead," in which only incineration kills the fuckers off). The mystery element is definitely key, and I think it's often to a horror film's disservice that it explains every. little. thing. to the audience.

ReplyDelete