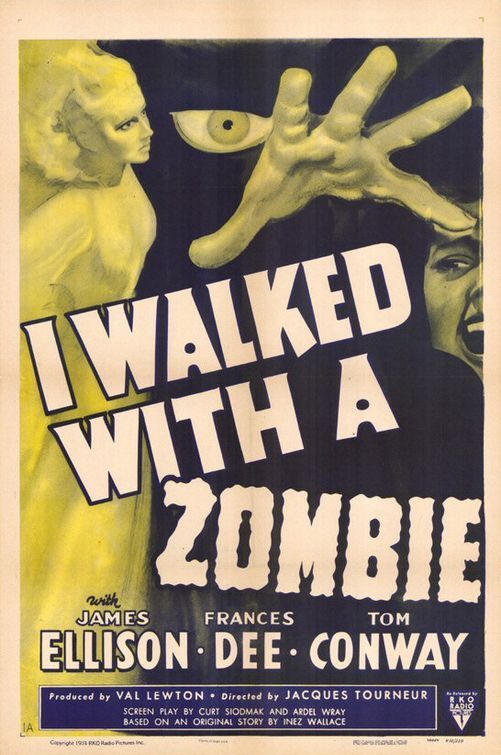

When Val Lewton was made head of RKO's horror unit in 1942, his newfound and artistically encouraging presence allowed for a breed in striking contrast the popular films of the day. Although quite often excellent in their own right, Universal's output had long since become it's own name brand complete with predictably filled expectations and built-in mass appeal, and one that was on the tipping point between the methodical and the self-parodying. Lewton's emphasis on mood and context was more suggestively menacing than outrightly terrifying, and his work with the similarly daring Jacques Tourneur made for some of the most memorable (and, despite their relative uniqueness, lucrative) films of the decade. I Walked with a Zombie may be their most prolific work together, a miniature masterpiece of contorted human emotions and uneasy personal broodings emphasized by a gothic melange of sight and sound. The film was marketed not unlike The Wolf Man but its sense of horror is rarely of the visually recognizable kind; the creature alluded to in its title is not terrifying in a physical sense but for its implications on the human soul.

Tourneur lends a revolutionary gravitas to the film's representation of history and culture. Frances (Betsy Connell) has traveled to an island in the West Indies to care for Jessica (Christine Gordon), the catatonic wife of plantation owner Paul Holland (Tom Conway). Her condition bears scientific explanation in its origination from a debilitating fever, but the servants - descendants of the slave population imported generations ago - refer to the unresponsive woman as a zombie, neither dead nor truly alive. Strains between Paul and his brother Wesley (James Ellison) originate from their former love triangle with Jessica, while blame for her state circles around the family like an unseen vulture. Tourneur ravishingly evokes these dagger-esque conflicts with the depth of his mise en scène; Venetian blinds cast shadows that cut to the core of these internalized pangs, while his characters move across the frame not unlike disembodied spirits.

Tourneur lends a revolutionary gravitas to the film's representation of history and culture. Frances (Betsy Connell) has traveled to an island in the West Indies to care for Jessica (Christine Gordon), the catatonic wife of plantation owner Paul Holland (Tom Conway). Her condition bears scientific explanation in its origination from a debilitating fever, but the servants - descendants of the slave population imported generations ago - refer to the unresponsive woman as a zombie, neither dead nor truly alive. Strains between Paul and his brother Wesley (James Ellison) originate from their former love triangle with Jessica, while blame for her state circles around the family like an unseen vulture. Tourneur ravishingly evokes these dagger-esque conflicts with the depth of his mise en scène; Venetian blinds cast shadows that cut to the core of these internalized pangs, while his characters move across the frame not unlike disembodied spirits.After learning of the voodoo rituals that take place on the island, Frances thinks it possible that Jessica might be cured by their practices; though in love with Paul, she would rather see him reunited with his wife than forced to reckon with the love of another. In the film's most alluring sequence, Frances sneaks off to the nightly ceremony with her patients, their figures moving ethereally through the plantation fields before confronting the wide-eyed zombie Carrefour (Darby Jones). The ritual itself is one of pounding performance art, with Tourneur granting the portrayed congregation due respect (as opposed to the hokey representations most non-Christian religions received at the time); although religion is a force largely absent from the film's interpersonal conflicts, the voodoo Gods seem to speak through the surroundings themselves. Social customs and local histories imprint themselves on the present, guiding not only rituals but modes of anguish and self-destruction. Frances and Carrefour's zombies are often compelled by external forces but it is the lot of the film's characters who are seemingly bound by fate.

Feature: 31 Days of Zombie!

No comments:

Post a Comment