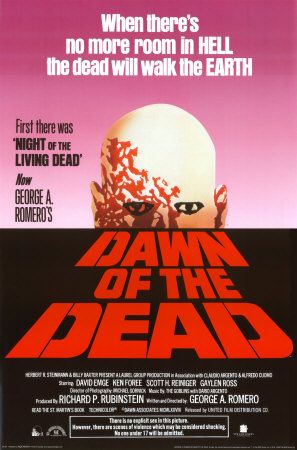

Much has been written about George Romero's Dawn of the Dead – more, perhaps, than any other horror film ever made, given its much-deserved critical/cultural standing and expansive opportunities for academic investigations. Night of the Living Dead was a hit upon its initial release but its success came slowly through word of mouth on the nickelodeon circuit. Ten years later, Dawn of the Dead was ready to capitalize on its predecessor's already extensive influence, and thus a brilliant film was granted the luxury of finding its audience immediately. I myself have seen the film around a half dozen times or so over about ten years, first renting it sometime during my pre-adolescence, after having been blown away by the bleak, unflinching terror that was Night. My initial experience with Dawn remains something of a blur; gore and blood abounded, for sure, and given both my age and the still-potent trend setting nature of the film, my sense is that it was something of a sensory overload (and to think it was on a scratchy old pan-and-scan videotape).

Very clear, though, is my memory of the film's most infamous piece of dialogue; though I myself am not as huge of a supporter of the film as many are (though a near-masterpiece, it is easily my least favorite of Romero's original trilogy), I believe it contains the finest single moment in the director's zombie pantheon. Fleeing the metropolitan areas overrun by the exploding zombie populace, our protagonists land their helicopter at a shopping mall in search of food and supplies, only to find the place overrun with the mindlessly wandering undead. Wonders Francine (Gaylen Ross), "What are they doing? Why do they come here?" With a dry wit that even he may not be privy to, her boyfriend responds: "Some kind of instinct. Memory, of what they used to do. This was an important place in their lives." Even at the age of ten, I recognized the implied criticism of meaningless reliance on commodity to define oneself, even if the concept itself was temporarily beyond my articulation.

Very clear, though, is my memory of the film's most infamous piece of dialogue; though I myself am not as huge of a supporter of the film as many are (though a near-masterpiece, it is easily my least favorite of Romero's original trilogy), I believe it contains the finest single moment in the director's zombie pantheon. Fleeing the metropolitan areas overrun by the exploding zombie populace, our protagonists land their helicopter at a shopping mall in search of food and supplies, only to find the place overrun with the mindlessly wandering undead. Wonders Francine (Gaylen Ross), "What are they doing? Why do they come here?" With a dry wit that even he may not be privy to, her boyfriend responds: "Some kind of instinct. Memory, of what they used to do. This was an important place in their lives." Even at the age of ten, I recognized the implied criticism of meaningless reliance on commodity to define oneself, even if the concept itself was temporarily beyond my articulation.Watching the film once again, Romero's carefully calculated deconstructions on social woes of the time seem most brilliant in their simultaneously identifying the film as a distinctly American work rooted in the cultural anarchy of the 1970's as well as one packed with universal truths on the human condition, borders of time and place notwithstanding. The former packs the greatest punch in the third-act war between the main protagonists holed up in their shopping mall fortress and the military convoy that overruns them (bringing the zombie population flooding back in), stealthily evoking not simply the tensions between pacifist movements and more aggressive social orders of the time, but any scenario in which men turn on each other in the face of greater disorder (in other words, look at any historical timeline and pick your example of choice). The latter, then, is one implicit in the passive social hierarchies throughout Romero's screenplay, particularly amidst relationships and connective tissues so obvious they tend to remain hidden in plain view. In a prolonged television debate meant to inform viewers on how to handle the crisis at hand, a lone scientist stresses the importance of exterminating the dead "without emotion." How fitting, then, that the soldiers who underestimate the zombies – treating them more like disposable hunting targets worthy of ridicule than a lethal force to be reckoned with – are generally those who find themselves being torn limb from limb.

Romero's staging of these sequences is deliberately jarring in their sense of physical placement and spacial relationships, a quality that often renders his montages aggravating and underwhelming in the moment, only to improve immeasurably in a more contextualized retrospect. The opening sequence of a television station in disarray is a nearly unsurpassed example of cinematic crisis in the moment, while the subsequent raid on a zombie-infested apartment complex is by turns overwhelming in its chaos (two words: exploding head) and necessarily off-putting in its perpetual state of confusion. Romero's framing of social ills via his rotting, walking metaphors is ingenious but it's the more subtle, unspoken statements that register with the greatest force. Along with Peter's (Ken Foree) passive rip on America's mallrat culture, a personal favorite touch comes late in the film, after our characters have locked off their place of residence and cleared it of any danger, now lavishing themselves with unnecessary material goods galore while the world goes to shit beyond their decorated walls. Francine, decked out in makeup and channeling heroines of the silver screen with her sexy six-shooter, is briefly juxtaposed with an identically lavished mannequin (the moment may very well be her inner self-realization), plasticine and utterly devoid of anything human. This lies at the core of our character's moral reawakening and the reclamation of their identity apart from the material. In other words (to quote Marylin Manson), without the threat of death, there's no reason to live at all.

Romero's staging of these sequences is deliberately jarring in their sense of physical placement and spacial relationships, a quality that often renders his montages aggravating and underwhelming in the moment, only to improve immeasurably in a more contextualized retrospect. The opening sequence of a television station in disarray is a nearly unsurpassed example of cinematic crisis in the moment, while the subsequent raid on a zombie-infested apartment complex is by turns overwhelming in its chaos (two words: exploding head) and necessarily off-putting in its perpetual state of confusion. Romero's framing of social ills via his rotting, walking metaphors is ingenious but it's the more subtle, unspoken statements that register with the greatest force. Along with Peter's (Ken Foree) passive rip on America's mallrat culture, a personal favorite touch comes late in the film, after our characters have locked off their place of residence and cleared it of any danger, now lavishing themselves with unnecessary material goods galore while the world goes to shit beyond their decorated walls. Francine, decked out in makeup and channeling heroines of the silver screen with her sexy six-shooter, is briefly juxtaposed with an identically lavished mannequin (the moment may very well be her inner self-realization), plasticine and utterly devoid of anything human. This lies at the core of our character's moral reawakening and the reclamation of their identity apart from the material. In other words (to quote Marylin Manson), without the threat of death, there's no reason to live at all.Feature: 31 Days of Zombie!

Excellent post, Rob. You've articulated a lot of the things that make this movie one of my favourites.

ReplyDeleteBut for my money, the best part in the whole movie is right at the end, where Peter decides he can't take it anymore and lets Francine go off on her own while he walks off to blow his brains out. And then, just as the dead are closing in and he actually has to do the deed, he goes "Nah! Fuck it!" and fights his way to freedom and an uncertain future.

With the music rising and Peter kicking some zombie ass, it's an incredibly cheesy moment, and Romero's original bleak ending might have been more thematically pleasing, but it still makes the whole movie for me. Coming after all the death and blood and gore, to see somebody actually choose life amidst death, to survive and go on, it's a moment of pure beauty. A small ray of light that still manages to balance out all the horror and despair.

Happy endings, even ones as ambiguous as this one, might be seen as awfully commercial, but in horror movies, and zombie films in particular, going out on the odd positive note can be fantastic.

Actually, it's not the military that overruns the four protagonists' mall-fort in the film... it's a rag-tag biker gang of survivalists... and Romero's comment on who survives the zombie apocalypse is telling. At one point Peter (formerly of the Philly S.W.A.T. team) proclaims his small foursome of survivors "thieves and bad guys" as they're doing nothing to achieve victory over the zombie threat by banding together with others... instead they run and ransack the mall themselves before a threat greater than the zombie hoards shows up and challenges our protagonists' control of their mall environment. This biker gang is the symbol of pure anarchy in the face of chaos... at least the four characters we grow to love over the course of the film try to maintain a semblance of the society that is slowly being "eaten" away... the biker gang could care less for the world that was and has no ideas for building a better future or collectively cooperate to fight against the zombie threat... this is Romero at his most misanthropic, basically saying (as Fran does in one sequence) "we're losing it ourselves."

ReplyDeleteThey are but a gang of bikers, but their essence strikes me as that of a military unit without order or purpose, other than to feed and amuse themselves (the term was meant loosely anyhow). But yes, our foursome of protagonists - even if they are "thieves and bad guys" - are far from violent to each other, at least without necessity (such as Roger's actions during the apartment raid). They're pacifists lined with the common sense that violence is sometimes necessary. But with the bikers, I agree totally - if you're not misanthropic in the face of that (i.e. America in today's world), then your commitment to optimism has crossed the line into dangerous naivety.

ReplyDeleteI agree with your clarification... Romero writes intelligent films for intelligent moviegoers and often there's a lot of backstory he only implies or hints at that can be easily filled in by the viewer. I agree that the biker gang could stand in for the military acting without purpose (and boy is that ever so relevant at the dawn of the 21st century), in fact with Romero's zombie apocalypse in full swing in "Dawn of the Dead" these bikers could easily be AWOL soliders running from the collapse of society much like Fran, Steven, Peter and Roger do, only without remorse and a sense of enthusiasm for the end of society and it's rules.

ReplyDeleteI'm really enjoying your site and the zombie bloggin' you're doing. Nice insight and personal touches on the viewing of these films (and others outside of the horror genre and zombie apocalypse sub-genre).

Something truly lacking in modern horror films is eminently present in Dawn Of The Dead - characters. Ones you can relate to. Ones that you can feel like you could interchange with. Ones that make you wonder "what would I do in their place?"

ReplyDeleteThe moment for me that this first hits is when the mall is locked up, and in the words of Peter, "we're going on a hunt". We then go back to Francine locked safely inside J.C. Penney's as the remaining zombies wander about. In the background we hear nothing but shots ringing out, understanding that the zombies are about to die.

A softball uniform-class zombie at that point comes over to Francine and falls into a sitting position to look her in the eyes. In his face, you can read the confusion and pleading with her not to be saved, but "what-is-going-on?". Francine looks at him, and her face is heartbroken, and for a minute, you actually feel sorry for the zombies - they didn't ask for this to be done to them.

Newer versions do not make any distinction between us and the monsters, but Dawn Of The Dead makes us feel who these people are - both the living and the dead.